Featured Golf News

Miura Clubs - Quality Control is the Key

I remember Karsten Solheim telling about his days as a Seattle shoemaker during the last Great Depression, and how he emerged victorious with the other three cobblers on the busy corner. "I raised my prices," he said. "I had a better product and people realized it once I charged more. The others went out of business."

Solheim went on, of course, to change the face of golf clubs with his line of PING products. Which brings us to the $600 driver from Miura, not to mention the $300 hybrid or the set of forged irons that retail between $1,600 and $2,200.

These are clubs the makers consider a work of art, clubs that are classic and so good they've been in the hands of players winning major championships even while they were under contract with the producers of another product.

Miura isn't new, although the 50-year-old Japanese club-making company is new to North America with its headquarters moved to Vancouver, B.C. The company hired Golf Channel business reporter Adam Barr as its president.

The Miura Driver

"My job has always been to tell stories," said Barr. "Now I'm telling the story of Miura to a new audience."

Miura will never rival the large club manufacturers, and wouldn't produce what it does if it did. But there is a market - as Solheim proved on a Seattle street corner - for a carefully crafted product, one where money is invested not in advertisement and endorsements, but in serious quality control.

It all began in the 1950s in the Japanese seaside town of Himeji, noted for its high-grade steel and its history of producing the swords of Samurai. There seems to be a certain Zen that comes over you when you put a Miura forged iron in your hands, knowing - or not knowing - it underwent a 14-step forging process and was cared and caressed enough to ensure precision.

In an earlier time, you paid top dollar for a Nikon camera lens because you knew it wasn't mass-produced, that quality control had eliminated flawed products. You were paying, in a sense, for the lens you didn't get - the defective one - while getting the one that did work.

That's some of the appeal of Miura. Mostly, it's the feel of a handcrafted product that doesn't issue a new, improved club every year, that in some ways is essentially what Katsuhiro Miura first forged as a 16-year-old. He started the company at age 23 and now, nearing 70, still works in the factory in Japan, his legacy passed daily to his two sons.

The Miura irons are distinctive because the hosel is made separately from the club head and isn't married to the club until the sixth stage of forging. The factory produces only 500 or so clubs a day and those are forwarded for sale only after they have met specific standards.

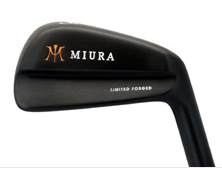

The Miura LG Black Blade

Miura is now producing a full-line of clubs, not just irons. The Miura driver is a full 460cc but has a higher face on the club and doesn't look as large and cumbersome as other expensive drivers. It seems only fitting that the Miura driver is understated with a matted black finish as opposed to the white finish of the TaylorMade drivers. The most expensive Miura irons are black, too.

Barr said price usually isn't the issue with those buying Miura clubs, and that the original investment makes sense if you play the clubs over an extended period of time.

There are now more than 100 dealers in the U.S. selling Miura clubs. The www.Miuragolf.com website has a locator map to find one near you.

"People need to feel the club in their hands," said Barr. "They tell us the driver is longer when we didn't design it for that.

"Maybe they feel confident with the driver, swing easier and get more distance."

Blaine Newnham has covered golf for 50 years. He still cherishes the memory of following Ben Hogan for 18 holes during the first round of the 1966 U.S. Open at the Olympic Club in San Francisco. He worked then for the Oakland Tribune, where he covered the Oakland Raiders during the first three seasons of head coach John Madden. Blaine moved on to Eugene, Ore., in 1971 as sports editor and columnist, covering the 1972 Olympic Games in Munich. He covered five Olympics all together - Mexico City, Munich, Los Angeles, Seoul, and Athens - before retiring in early 2005 from the Seattle Times. He covered his first Masters in 1987 when Larry Mize chipped in to beat Greg Norman, and his last in 2005 when Tiger Woods chip dramatically teetered on the lip at No. 16 and rolled in. He saw Woods' four straight major wins in 2000 and 2001, and Payne Stewart's par putt to win the U.S. Open at Pinehurst. In 2005, Blaine received the Northwest Golf Media Association's Distinguished Service Award. He and his wife, Joanna, live in Indianola, Wash., where the Dungeness crabs outnumber the people.

Story Options

|

Print this Story |