Featured Golf News

Robert Trent Jones, Jr. Interview

In the novel "Slim and None," Dan Jenkins quipped that Oakland Hills C.C. was tougher than any course "designed by man, ghoul, or Robert Trent Jones." Indeed, Trent's reputation for being a great gentleman was only equaled by his reputation for building murderously penal golf courses. Playing with Trent, Jimmy Demeret once joked, "Hey Trent! I saw a course you'd love. You stand on the first tee box and take a penalty stroke."

I used to feel that way about Trent when I was playing for my boarding school golf team. Our home course, Crumpin-Fox Club in northwest Massachusetts was a jungle Joseph Conrad would have feared. Day in and day out that brutishly long, watery, forested and narrow back nine was a merciless minefield of unexploded triple-bogeys: it was torture for high-schoolers. The course won the battle every single day.

As we all know, the apples fall close to the tree, and Bob Jr. and Rees have carved out careers that have garnered great acclaim, but are also stereotyped. They have a penchant for building tough courses and sharpening tournament venues as well. The Jones family name has been synonymous with royalty in golf-design circles for decades, but also with misery on the handicap card.

So imagine my surprise (and the surprise of other golf architecture aficionados) when we read this list of great holes analyzed by Robert Trent Jones, Jr. is his book "Golf Design." His chapter on "Architectural Excellence" contains the following examples of great architectural strategies:

The Eden Hole - No. 11 at St. Andrews

The Redan - No. 15 at North Berwick, No. 4 at High Pointe

The Doctrine of Deception - No. 5 at Royal Portrush (Dunluce Links), No. 5 at San Francisco G.C., No. 13 at Pine Valley, No. 3 at Riviera.

The Cape Hole - No. 5 at Mid-Ocean Club

Diagonal Angles - No. 13 at Baltusrol, No. 16 at Harbour Town

"Half-Par" holes - No. 13 at Augusta

He then writes, "Accomplished designers listen to the land and tailor the course to it."

Wait a minute! Is this Robert Trent Jones, Jr. or Tom Doak? Look at all those strategies that come straight out of C.B. Macdonald, Seth Raynor and Charles Banks' playbook! Did I get lost and interview Brian Silva by accident? No, but a funny thing happened on the way through the interview. I thought I was interviewing the scion who put penal architecture in vogue for decades. Instead, he gave us his thoughts on Chambers Bay and the coming 2015 U.S. Open, reminisced about some of his influences, dissected the doctrine of "Minimalism," and issued a friendly challenge to Tom Doak (while praising his Redan hole at High Pointe at the same time).

So let's get into what we discussed.

JF: Who are some of your favorite architects?

RTJ: Tillie (A.W. Tillinghast). Great golf course architects fit the golf course to the land, and he's probably my favorite of the dead architects. His bunkering is flamboyant but you can see what you're supposed to do to avoid them, and if you get in them you can get out of them. Sometimes he built pedestal greens and set the bunkers into them above the natural grade because he was building on granite (like Winged Foot), while out West, at San Francisco G.C., for instance, he built them below the natural grade or at grade level because he was in sand.

You see, the look and strategy of a course is a function of the soil type. Sand drains vertically and clay drains much differently. Dad said the three most important technical principles of golf course architecture were drainage, drainage and drainage. So if you're in rock or clay, you build the features of the course above the natural grade, so that's where Tillie put the bunkers on those courses. In sandy soil like the U.K. the dunes are hummocks above grade, and the bunkers are gathering bunkers below grade, which gather an area much larger than the raked sand.

JF: Nowadays if you do that (build bunkers that draw in golf shots), people scream bloody murder.

RTJ: Pete Dye does it.

JF: And I love it, but few others do.

RTJ: That's because the grassy area leading into the bunker can be used to increase the effective size. A basin can become a bathtub and vice-versa. When you can gather into a bunker using tightly mowed turf, you affect a much larger area to catch a shot hit off-line. So that narrows the landing area further than it looks.

JF: What about Tillie's penchant for building the "great hazard" bunkers at many of his courses? Isn't that a great feature we should try to bring back more often?

RTJ: Ah! The "tarantula" at San Francisco Golf Club! It's either 14 or 15 and where the land gave him beautiful sandy soil, and even at places like Bethpage, he would do these beach-like bunkers mimicking the dunes-like bunkers abroad.

JF: Isn't that what the "glacier bunker" on No. 4 at Bethpage used to look like?

RTJ: I think so, I don't remember it that well. But I like blowout bunkers even more. They tend to be what's there naturally: literally, by the wind blowing off the sea, or like an ancient seabed in Nebraska or the strong winds of the plain states. At Chambers Bay we did blow out bunkers and hummocks (indicating a picture).

JF: Now those look like berms that Seth Raynor did at flat courses like the Country Club of Charleston or some of those older courses from the aughts and teens.

RTJ: True. They're the same thing as hummocks, and you can see how at Chambers Bay, we've re-crafted how the wind came off Puget Sound from the north and would have deposited the sand. Now the flagstick positions there are what we call in the industry medium-sized, which is actually comparatively small. Some of the greens are "large" size, but they are sloping and have softer but more sweeping transitions than the segmented "little decks" of say, Torrey Pines.

We moved one and a half million cubic yards of material to craft the dunes, hummocks, fairways and other playable areas, and then veneered the playable area as well, so that the entire surface is like a sandy green in condition, playing firm, where the ball runs out on the ground. It is NOT target golf.

The site was a mined-out quarry over 100 years old for sand and gravel for roads. We're on 250 acres out of a total 600 acre in the mined-out area. As golf designers, we'd kill for sand, and here's a quarry! So we continued mining it. We took the sand and screened it to get all the stones out - then re-crafted the site. We mined it to get some better views of Puget Sound and we designed a terracing effect, where some holes are above others.

JF: They did that at Bayonne and Tall Grass. It also helps save space.

RTJ: That's right, terracing can also save space. And I really liked Bayonne, by the way. You see, the best courses are on sand, but that's rare, like the coasts and the middle of Nebraska. It's easy to work unspoiled, sandy land.

Now we have created something new at Chambers Bay called "ribbon tees." Instead of separate tees, think of a wrapped Christmas present that's tied by a long wide ribbon. The tees are long, with little folds and irregularities as they run along seamlessly, connected to the fairways. The tees are integrated against the dunescape, but they are at different lengths and angles and flow through different grades as you go from tips to the forwards and the various markers in between. They are a cross between a free-form tee and walking path.

Ron Whitten gave us a nice compliment when he said the tees are the first creatively new idea of the original 21st century. It's "into" the land and "of" the land - eminently natural - and it doesn't feel like a tee "box," and you have a many options for the markers. They may, however, be canted, so watch out. Find the place within the markers where it's flat or where you can use the grade to help shape your shot. We wanted to try that experiment. I bet in the ancient days the tee boxes were wherever they could find them, flat lies or not. But the idea is functional, beautiful and natural. On the same hole, a different golfer with a different shot shape can hit the shot called for, or if he can't, he can find another place on the tee to shape his shot the way he'd prefer. There are no cart paths - thank the golf gods we didn't have to put black strokes of paint on the Mona Lisa. Chambers Bay is wide - everything is lateral - with 200 feet of up-and-down elevation change but completely open, with only one tree.

JF: What strains of grass are there?

RTJ: Fescue grass from tee to green and in the fairways and a little bit of bent for body on the green. Since people fight over green speeds, what we did at Chambers was to use grass you can't ramp up to 14. The best you can get it to is 10. Fescue and sand make for hard surface - no ball marks - there's that thump when the ball hits. Also, it allows the architect to keep the rhythm and flow to be one complete hole, no segmentation from tee to fairway to green.

Now the ball runs out, so you have to anticipate that. I'm excited about the U. S. Open there because Chambers Bay will ask the best players in the world to think! I'm in their brain, they are on the defensive, and that will separate the truly skilled players and thinkers from the home run hitters and the big-hitting limber backs. Another way we do this is to put bump-and-run shots back in play. If the terrain makes the pros think, they may freeze up. When we worked the site during construction, Beethoven's Ninth was coursing through my veins and I thank the leadership of Pierce County for being brave enough to bless these ideas.

JF: Why haven't we seen a design like this before from you?

RTJ: It's hard for owners to overcome their predispositions. People like what they've seen before and, as you said, they are afraid of change because that vision gets in their heads. Some designers take risks and they might not get the best reception, but you have to take risks. You can be different and still be dull, but you can also be different and unforgettable.

JF: Like Mike Strantz

RTJ: Yes. Strantz was different, but unforgettable. The work he did in South Carolina was stunning. He was an artist. There is a difference between golf architecture and golf art. Eighteen sticks on a field is not architecture. Drainage, irrigation and maintenance, that's the science of architecture, but the art is inextricably linked. That's why Strantz was so good. Even his early work was flamboyant, yet appeared to flow so well with the land. He used the indigenous landscape brilliantly and crafted features, particularly the bunkers, which looked as if they could have been there naturally. Tobacco Road is a terrific course, with its blind shots. I like occasional blind shots, but you never hear the end of it when you put them on a course. Now you have to give the player a little bit of green or something to aim toward.

Strantz understood that you need the artistic as well as the scientific and strategic. One problem with golf course design is people care too much about conditioning and the natural setting being too important for the ratings - that doesn't mean those aspects - if it gives you pleasure and relaxation, that's apart of the game too. When you're shooting 100, you can still enjoy the day, but great golf courses shouldn't only be judged by their sites alone, the skill and craftsmanship lie in the way it's built. That's why Tobacco Road is so good.

Also, what Strantz did at Monterey Peninsula Country Club was masterful. I played the course with other golf architects and we were looking at the craftsmanship of the target bunkering, and it gave us the impression it had been there forever. There are great lines for shot-making and choices on diagonals. I love diagonals, not sharp doglegs. What a huge loss to the game that he died so young. His work was truly new stuff.

That's the same idea we had at Chambers Bay. I want the player to feel agony and ecstasy. I want them to be emotionally involved with the golf course.

JF: How long have you wanted and waited for a site like that?

RTJ: Well, I've had other beautiful and dramatic sites that had unique character, such in Korea at Rainbow Hills.

JF: That looks like Princeville.

RTJ: It's more severe than Princeville. There's another called Ostar C.C. (South Korea)

JF: How about in America?

RTJ: Princeville. On the Prince Course, quite a lot of earth was moved, basically 600,000 cubic yards. While the Princeville course built 20 years earlier moved 250,000cubic yards

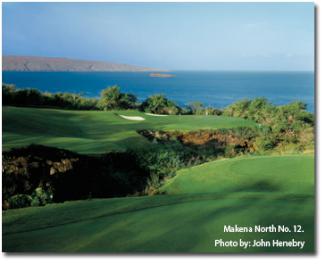

I also like a strategic and artistic bunkering principle called the "principle of harmony," where you recreate or mimic a natural feature of nature in background of the shot, like a mountain or island, the foreground with a man-made shape in sand, or mounding or pond on the golf course. Take for example, 12 at the Makena North Course in Makena, Hawaii, where I made a bunker shaped exactly like an offshore rock, but it also served a strategic purpose because the green is a promontory out in the ravine edging the ocean. earing the ravine, people aim right at the bunker.

JF: Pete Dye does that all the time, too.

RTJ: Yes he does . . . now remember, even if you're not playing well, you'll always be filled with the glory of the courses' beauty.

JF: What are some of your other favorite courses?

RTJ: Winged Foot. I like both East and West. I played in the Anderson when I was young, once with Allan Gilleson. He went to Yale with me and we both played golf at Yale together, so we entered the Anderson together as Elis.

Bethpage, of course, is another Tillinghast, as is the Lewiston, N.Y., course near Niagara. You see the same bunkering styles, large flamboyant, bracketing or fronting the greens. He was a great router, following the land.

Also Baltusrol, lower set in a Jersey meadow, or Ridgewood, which is natural, like Winged Foot. Tillinghast believed if you had trees on a site like those courses the trees themselves were natural hazards, vertical hazards

JF: Hasn't that gotten out of hand now? Didn't people, like members of these clubs, come along and add a lot more trees during "misguided beautification" campaigns and change the strategy of the course altogether?

RTJ: Which made them look like cemeteries rather than golf courses…

JF: What's the first duty of a golf course architect?

RTJ: Let's define the word "architect" - a designer crafts a design that's already there, as a jeweler extracts the gem from the stone. Take Minimalism, as a doctrine, though Minimalism has no meaning - it's like any ism has no meaning. You can't have Minimalism in a Maximist site, can you? Like Japan? Or Korea? Or Colorado? Or any mountainous site from Maine down through the Alleghenies, or throughout the Rockies, and so on. It's a little like "are you a vegetarian or a vegan?" What extent do you go to get the health benefits?

Now one important aspect of architecture is to look at the underlying philosophy of the design, and those who execute it. The shaper is every bit as important as the designer. Perimeter-weighted fairways, for example - where the ball kicks inward, a containment philosophy - it's forgiving, like an oversized tennis racket for poorly struck shots, but it's a playable philosophy.

JF: Like Jim Engh does.

RTJ: He does, and to great effect. It rewards shots that are not executed well - which I don't agree with - but on munis it speeds up play for the average golfer. The opposite is the rejecting fairway or green, like a crowned green favored by Donald Ross and at, times by Pete Dye. The original Pinehurst courses are a good example for Ross.

JF: What do you think about Ross? You grew up on Montclair Golf Club.

RTJ: I don't like the rejection of a good shot as a player. So I'm not a Ross fan, even though I grew up at Montclair, New Jersey, and liked Montclair Golf Club.

Now, sometimes balls roll off of fairways because they're on granite or clay, for example the 6th hole at Stanford University in Palo Alto, California, and a few holes at Yale near New Haven. Now Minimalists simply lay the course on the land as they found it. You could call that Minimalism, but I call it chintzy.

JF: So you're saying Minimalism has a point of diminishing returns?

RTJ: Yes. You can craft a site to feel naturalistic - Chambers Bay does that. A better example is Keystone Ranch, a resort course in Colorado. We didn't have much money, a low budget. But if you're a good router - and my father was very good and he taught me - you can craft a natural site that stays true to the lay of the land and also highlights its natural features with bold accents and contours which are functional, even challenging. It's like the way a sculptor would work.

JF: How about Tom Doak?

RTJ: Fifteen years or so ago, I played his work in Northern Michigan and it was quite good. I love T.S. Eliot, [the great American the poet of the "Lost Generation"]. Eliot apparently plagiarized someone else's words and when the interviewer asked him, "Why would you borrow someone else's words?" he replied "Borrow? Hell I stole it. Good poets borrow, great poets steal." Meaning he could learn form someone else work and re-crafted a few words to make a new poem.

JF: What's that got to do with Doak?

RTJ: In his remodeling work, for example at The Valley Club in Santa Barbara, he borrows the styles of Mackenzie. At San Francisco Golf Club he borrows Tillie. And now MacDonald in Oregon.

JF: Isn't that a compliment though? If he's remodeling or renovating in the style of the original and it looks like the original architect's work, isn't that what he's supposed to do?

RTJ: Yes and no. When those styles were in vogue, they were playing with wooden-shafted clubs and balls that were imperfect. In the 21st Century, new defenses will be created by master architects in keeping with the way golf is played in our time.

JF: But I know for certain that that's exactly what he tells courses that ask him to restore. He says restoration to the original and keeping the course tough on the best players may be mutually exclusive. Then he does what the course asks him to do after he presents them with several logical courses of action that maximize as much of either principle as can be salvaged in this conundrum.

RTJ: That is what most professionals do - give the client what they want. But every once in a while, a new paradigm can be created and a great golf architect will know when to build on the traditions but create something wholly unique and new when the site is worthy of improvement. Maybe Doak's done his Beethoven's Fifth Symphony - Pacific Dunes, or I hear Ballyneal. But I believe our work at Chambers Bay is akin to Beethoven's Ninth - as Beethoven famously said, "Not these notes," meaning he was not using the chamber music of Hayden and Mozart, performed in wealthy homes, but creating a new music for all the people, like great Soul music of today which lifts peoples spirits and urges them on to join in joyfully.

JF: Why isn't Pacific Dunes for the people?

RTJ: Meaning all the people, open to players of all abilities, such as a muni like Bethpage, not a resort, like Bandon.

JF: Hmm . . . you're throwing down the gauntlet on Doak. You know he might respond.

RTJ: I hope he does. Think how good for the game it will be when he does build a muni as good as Chambers Bay or Bethpage. The game and all players will be better and more enriched for it. I look forward to a home and home game with him.

JF: He's redesigning a muni in Colorado called Common Ground.

RTJ: Well then I'll have to see it. Some architects don't like to get out and see other people's courses, but I want to see what everyone else does.

JF: So have you learned anything from Doak or is there anything in particular that you like?

RTJ: What I've learned from Doak? Well one of the things I like the most is that he realizes that a designer needs great people around him, and Doak not only has good people, but he gives them a lot of credit. Also, when they get onto someone else's style, they are faithful to it in their restorations. Many of his original works are situated on great landscapes. When the land is as beautiful as New Zealand, you don't have a lot to do. I prefer his early work, such as High Pointe, which we played together, as well as Crystal Downs. It is a little rough, and yes, the more he practiced, the better he got, by softening and refining his ideas while making courses more playable for everyone. He also has a great patron, Mike Keiser, and that makes all the difference.

JF: For my public golf readers, tell us about some of your favorite courses of yours to go and play.

RTJ: Well, Arrowhead in Littleton, Colorado. We built the whole thing for under $500,000. Those were tough times, a recession in the early '70s. Again, we crafted the course on land that was a geologic wonder. We laid the holes over, among and around all those great stone uplifts. The course was simply built, but choosing a routing was tough since there were so many options. Number 13 plays through that beautiful natural amphitheatre of rocks - I nearly got bitten by a rattlesnake on that hole - and the course sort of builds to a crescendo, and ends with that natural water hazard on 18, I didn't build that. It was already there.

Go see Three Crowns in Casper Wyoming. That was a degraded site owned by British Petroleum, it was such a bad site the Platte River caught fire in the '50s. We helped the owner clean it up for public play. In Maine there is Sugarloaf near Carrabassett, which the town owns. We met in the Boston Public Library because rooms were free there and we used to have meetings and used to get "shushed" by the librarian.

JF: How has your design philosophy changed over time?

RTJ: If you mean by style, I think there are golf courses which are 18 flags, on a nice field which is a sporting park. Some are simple, even in Scotland, on inland sites.

Then there are intentional designed characteristics you can implement on the ground - penal, strategic, heroic - that's architecture. You have a concept like one of these schools, and you have your style for that particular course. Then you come to golf art, what the person who is crafting it feels and how it serves both artistically and functionally. There is universal beauty - for example, the Winged Foot clubhouse, which is gorgeous and gothic, made from the natural field stone with its slate roof. Now other clubhouses are well designed and function well too, but you feel like you're in an office building, it's totally utilitarian. In architecture that difference applies.

"Occasionally when you combine all these aspects at a special place: Pine Valley, S.F.G.C., Cypress Point, it's gorgeous in any direction, but it's not just the setting that frames the golf course site. Pine Valley has a manmade lake, but they did it so artfully, it's gorgeous. At S.F.G.C., you're in the city, but the bunkers, the trees and the routing are all beautiful. They all have golf art - an ephemeral characteristic. That happens frequently with Tillie, but rarely courses of some other architects because they're too functional and precise about the playing characteristics and, as a result, their courses don't rise to the level of art."

My first project was Silverado in Napa. As a player, I was pleased because of the diagonal angles, and the bunker patterns gave us interesting shots. Even at a young age, I didn't just scatter bunkers like marbles.

Now I have always loved beauty, I moved from New Jersey to New Haven to Palo Alto. It's beautiful here. I have redwood trees in the back yard. I have mountains and the sea nearby, the beauty attracted me. The same is true of golf course design, when I'm able to do it. It doesn't have to be a big budget place. CordeValle in San Martin, California, is an example of this: a beautifully crafted course in a mundane valley setting by California standards. But everyone has a great time, even though it's not on the ocean or in the Sierras. So I try to mimic nature and still be functional. Sometimes you get a Spanish Bay and a Prince site which makes it easier to create art, and the rest of the time, you make the most of what you are given.

So when we get a core golf site, we evolve more toward trying to create art, like Rancho San Marcos near Santa Barbara; no houses, beautiful site, which I'd rather do, than a heavily integrated housing project…

I'm still influenced by Dad. His spirit lives in me and his great golf works. I started with elevated greens, then went to low-profile greens, like Princeville, then heroic in the '80s, like the Prince course or Joondalup in Australia. Then I moved on to challenges beyond the game like Moscow Country Club in Soviet times, taking golf where there was no golf. Then, in the 1980s, we have evolved back to the future big bold links style - Spanish Bay, The National near Melbourne, and now with new innovations, like the ribbon tees. So I tried not to get stuck in one form. Beethoven wrote different types of music, I want to master many styles, while applying myself to the site and to the clients' wishes.

Since launching his first golf writing website in 2004, http://www.jayflemma.thegolfspace.com, Jay Flemma's comparative analysis of golf designs and knowledge of golf course architecture and golf travel have garnered wide industry respect. In researching his book on America's great public golf courses (and whether they're worth the money), Jay, an associate editor of Cybergolf, has played over 220 nationally ranked public golf courses in 37 different states. Jay has played about 1,649,000 yards of golf - or roughly 938 miles. His pieces on travel and architecture appear in Golf Observer (www.golfobserver.com), Cybergolf and other print magazines. When not researching golf courses for design, value and excitement, Jay is an entertainment, copyright, Internet and trademark lawyer and an Entertainment and Internet Law professor in Manhattan. His clients have been nominated for Grammy and Emmy awards, won a Sundance Film Festival Best Director award, performed on stage and screen, and designed pop art for museums and collectors. Jay lives in Forest Hills, N.Y., and is fiercely loyal to his alma maters, Deerfield Academy in Massachusetts and Trinity College in Connecticut.

Story Options

|

Print this Story |