Featured Golf News

The ‘Best New Private Course’ Battles: A Study in Golf Dichotomy

Some years, the courses up for awards are ordinary and open up to little anticipation and fanfare. But not in 2006. This year sees a bumper crop of world-class designs and a dizzying tornado of marketing and corresponding anticipation. Unbelievable amounts of money, time and knowledge were invested in reaching for the brass ring of golf immortality, and there were some excellent efforts.

While countless golf venues fail to make the quantum leap from “the next big thing” to “one of the best in the world,” happily, one course succeeded and will take its immortal place in the great pantheon of world golf. Ballyneal, owned by the O’Neal brothers (“Bally” means “place of,” therefore “Ballyneal” means “Place of the O’Neals”) and designed by Tom Doak, this course will wake the entire golf world with a thunderclap. The remaining top candidates – Dismal River, Sebonack, Bayonne and Liberty National – are also quite creative and have wonderful high points, too. Bayonne in particular is a superlative effort, especially when considering it was designed by a developer-turned-architect (Eric Bergstol) with only one other solo design (Branton Woods).

[Author’s Note: I have played each course except Sebonack. A great deal has already been written about this collaboration of Tom Doak and Jack Nicklaus. Nestled cozily between the legendary tandem of Shinnecock Hills and The National Golf Links, the course in Southhampton, N.Y., has been widely acclaimed and well-received.]

The Battle of the Sand Belt

Thousands of years ago, the Nebraska-Colorado border was oceanfront property. Millions of tons of sand have been amassed over eons and now cover an enormous area from the northeast corner of Colorado to the entire western half of Nebraska. This is a stark lonely lunar landscape: waves upon waves of white-pink sand crashing against each other like a roiling sea. The drive through the Sand Belt is a singular life experience. This remote, barren and forlorn region is truly other-worldly.

Yet all that sand makes perfect terrain for golf, the best site to re-create the fast and firm conditions of the great seaside links of the UK and Ireland.

A dozen years ago, Bill Coore and Ben Crenshaw christened the pristine area with one of the top five courses in the U.S. Sand Hills Golf Club in Mullen is a true links experience that accentuates the ground game. It was built with the least amount of earth movement and shaping. The two designers simply wove the holes and greens amid the sandscape, crafting a course that looks like a natural extension of its surroundings. It is not just a towering achievement, but a paradigm-shifting, generational-defining accomplishment. Every day at Sand Hills is a joyous celebration of golf, and awestruck multitudes come to pay homage no matter how long the pilgrimage.

These same reverent and excited golfers will now make their way to Ballyneal, which is not just a rejoinder from Doak to his dear friends, Coore and Crenshaw, but is every bit as epic an achievement as Sand Hills. It’s just more rugged. Ballyneal is located just on the edge of the sand hills where the waves are just a little smaller and farther apart than in the teeth of the northwest Nebraska’s maelstrom. Nevertheless, the similar lonely dirt road at Sand Hills runs six miles from the nearest paved thoroughfare to this heralded new course in the wilds of Colorado.

Ballyneal is holistic golf at its best. No tee markers, no yardages or “Kirby” stones in the fairway, no bells, whistles or buzzers. It’s a throwback to 100 years ago. Caddies are required and provide all distances needed beyond your own eyes. Like any true links, there are no trees and the wind can vary up to five clubs up or down.

Doak had some inspired moments here, most notably his routing which makes the most of both the endless dune vistas and rugged green settings, and with his adventurous, tumultuous green contours. The green swales are so severe that the speed is kept in single digits on the Stimpmeter.

His first hole features a semi-blind drive to a fairway guarded by a diagonal cross-hazard. Bite off as much as you dare. The par-5 fourth showcases both excellent horizontal movement of the fairway form side to side, creating good angles, and outstanding vertical movement in the earth, with terrific fairway undulation, which Doak considers “the soul of the game.” There are 18 flat lies on the course – one at each tee box.

The par-3 fifth hole saw the first hole-in-one ever recorded on the course: by Eddie Peck, the owner of the outstanding Black Mesa Golf Club outside Sante Fe N.M.

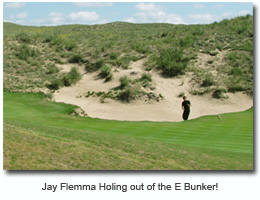

Nos. seven, eight and nine are also an interesting stretch. Seven is a short (300 yards or so) par-4 to a green in the shape of the letter “E” – with the negative space being a bunker. The closer you drive to the green, the worse your lie. Anything left will leave a shot sloping away from the player into the bunker. The par-5 eighth plays between some of the most towering dunes on the course to an enormous green with severe contouring. The ninth fairway was built by “the great meltdown,” as one member put it, removing sand between two ridges.

Finally, the par-3 11th features one of the most astounding optical illusions I have ever seen. The par-3 hole looks uphill both ways – from tee box to green and from green to tee box.

Ballyneal is so authentic and old-school that I felt as though I really was playing a century ago in a long-forgotten countryside. Players are so spellbound that with the right kind of eyes they can almost see the shadows and specters of golf antiquity traversing their way amid the dunes. Just how good is Ballyneal? If the opportunity arises to play it, golfers will come by brigades and won’t even stop to part their hair on the way out the door (the wind will rip it to shreds anyway).

Dismal River is a Jack Nicklaus signature course built in the shadow of Sand Hills. The layout represents the wildest design of any of Nicklaus’ efforts and has some world-class architecture, too. It’s a bit too severe in some places, but word is they are going to tone down these areas in the near future. The course also does not accentuate the ground game – which is a shame since all that sandy soil goes to waste, and makes the aerial attack the only option, making it even more difficult than it has to be. The targets here are too tight, despite having all the room in the world.

I like the start of the course the best since it feels the most natural, it’s the most subdued and features some of the best architecture you will see anywhere. The sweeping “S-curve” of the par-5 fourth is a textbook example of horizontal movement-creating playing angles. There is a tacky windmill there, the idea for which came right from Sand Hills, but unless you hit it, don’t lose sleep over it.

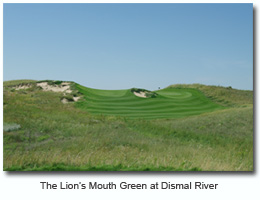

The second-best Nicklaus hole I have ever played is Dismal River’s par-3 fifth, which features a Lion’s Mouth green complex. A Lion’s Mouth is a bunker encircled by a horseshoe-shaped green. The putting surface is meant to be contoured so that one can putt around the bunker from one ramp to the other using the undulation. It’s one of the most rare and wonderful of Seth Raynor and Charles Blair Macdonald’s tricks imported from the UK, and it is refreshing to see Nicklaus’ team resurrect it here.

My favorite Nicklaus hole is the short, uphill par-4 sixth, which recalls the 17th at Alistair Mackenzie’s Crystal Downs. From the tee box, the fairway not only looks narrow but appears to slope so severely that the ball can’t possibly stay in the fairway. However, the secret of the hole is revealed when the player looks back from the green. The shapers cleverly built three hidden plateaus of fairway that will actually hold the ball with ease. Once again, the brilliance of the optical illusion takes a mundane hole and elevates it to classical status.

The contours of the fairways and greens start to increase in severity and speed as the rest of the course unfolds. Holes seven through 13 are downright tumultuous and the incessant requirement of aerial attack weighs heavily. If the speed of the fairways and greens is lowered, all of the contours could come back into play. But at double digits on the Stimp, approach shots simply don’t hold as well as they could.

While most people cite Dismal River’s 13th fairway – which is being fixed as we speak – my biggest issue is with the 10th, a par-3 with a bunker in the middle of the green. I am an enormous supporter of such a hole; the sixth at Riviera and 19 (yes, you read that correctly – 19) at Forest Dunes in Michigan are favorites mine since the green contours, like a Lion’s Mouth, feed a properly thought-out and well-struck putt around the hazard. The green swales and size here make a mockery of that template. Four- and five-foot swales were built willy-nilly, turning the hole into a caricature. It becomes a matter of pure luck whether one will make a par or a six. While some luck on a true links is welcome, give us a fighting chance.

From the 14th hole on, the course tones back down a bit and features solid design. All in all, Dismal River is a good effort, but needs more ground-game options. Still, it is a marvel and should be seen.

The Battle of “Joyzee”

Interestingly, there are also neighbors opening within each other’s shadows in the New Jersey just across from Manhattan. Bayonne and Liberty National are so close to one another, the guest of a Bayonne member actually took one wrong turn and ended up on the range at Liberty National, eating one of the club’s ham sandwiches and hitting 5-irons before he realized he was at the wrong practice facility. “The range and the ham sandwich were pretty good,” the surprise guest later recalled.

Bayonne is the 2005 Pittsburgh Steelers of the golf world. Nobody expected it to be this good, but then the backers went and crafted a masterpiece that everyone stood up and cheered. Basically, call it “Arcadia Bluffs East” as the course deeply resembles that marvelous public gem of an Irish links on the edge of Lake Michigan. Bergstrol piled up a staggering 7.5 million cubic yards of sand and built a berm around the entire property, giving it a welcome seclusion. This trick also worked for Doak at his wonderful Texas creation at “The Rawls Course.”

Bergstrol also employed a difficult but equally brilliant trick to shoe-horn the best design into the property: he terraced two fairways and built two tee-boxes with criss-cross drives. He embraced these issues and, as long as nobody hits a player on No. 8 with a drive from the ninth hole, the whole thing works triumphantly. (See Tall Grass Golf Club in Shoreham, N.Y., for another excellent example of terracing to fit a course on a tight site.) Again, excellent green contours complement an ingenious routing that takes full advantage of as many views of the property as possible. You have no idea you are in NYC until you arrive at the 14th tee to see the ocean liners being loaded up with passengers. Like Ireland, the wind is ever-present here except in high summer.

The opening holes are fascinating. The short par-4 first features a semi-blind approach to a dell green. The 90-degree dogleg second works since the second shot is played to a green set neatly into the side of a dune. The par-5 fourth plays through more towering dunes. The par-3s stretch in four different directions and showcase modified Redan and Biarritz green complexes.

Holes 12 and 13 form the mighty backbone of the course. The long par-4 12th plays through 13 bunkers (called Seven Sisters, Six Brothers) en route to the bayside. The par-5 13th climbs triumphantly back to the clubhouse. It would make a stirring finishing hole. In fact, I played this routing once, starting on the par-3 14th and loved it even more than the true order of holes. But most people might not like starting on a par-3. That’s sad and closed-minded as 13 is an even stronger closer than 18.

The finish is unbelievable. After hearing the deep, rich whistle of the liners, the short par-4 15th seemingly has no fairway among the heaving mounds, but hidden slivers are there to accept a fairway wood. The long par-4 16th plays back to the water and 17 along its edge. Both are strong par-4s clocking in at over 400 yards.

The course has a little of everything – it has a solid natural setting considering it’s in Northern Jersey, and the design is far more advanced than we could ever expect from a golf architect on only his second design. The greens and hazards look eminently natural despite being created from scratch. In short, Bergstrol did everything right.

Liberty National was also manufactured from scratch – with 1.3 million cubic yards of earth moved and about $100 million spent, but it looks artificial. Too many features from the 1980s rear their heads here: from overly narrow, penal fairways to flat greens to dreadful faux mounds lining holes (most notably, the fifth). The course is too long (the par-70, with three par-4s over 500 yards long, is 7,500 yards from the tips), too narrow and features a hit-or-miss routing. The good feature is that all wind directions and views come into play, but the fairways may be impossible to hit in a 30 mph crosswind.

The Liberty staff and owners will find everything I just said a compliment because their raison d’etre is to host a major championship or a Ryder Cup. As we know, such events seek something completely different from golf-architecture buffs. Also desirable is a course that looks good on TV and, “green contours be damned,” pros want to make putts. Why do you think Winged Foot is the hardest U.S. Open venue?

Liberty’s folks also want to attract the wealthiest clientele – prominently advertising Trump and Giuliani’s memberships, and that you can have foie gras, champagne or anything else you can dream about delivered to you anywhere on the course. Memberships are between $400,000 and $500,000, with Bayonne costing less than half of those tidy sums.

A Broad View

Ballyneal’s greatest success is that it was built holistically and looks eminently natural, blending perfectly within its surroundings. By contrast, Dismal River was built in a minimalist manner, but looks manufactured in a handful of places. The 10th green and 13th fairway are two examples. Still, once they tone these areas down, it will be an excellent course.

Bayonne is a triumph. Though it is entirely manufactured, it looks completely natural. Bergstrol created a dunescape by moving a staggering 7.5 million cubic yards of earth; the highest amount I have ever heard quoted for a new golf course. By contrast, at Liberty Bob Cupp and Tom Kite moved 1.3 million yards of earth. But that course looks completely artificial and doesn’t blend in well with the surroundings, most notably on the latter half of the front nine.

There is also a cultural dichotomy at work that underscores the difference in ideals for building private courses. The vast majority of golfers are not about foie gras and champagne, but bacon-and-egg sandwiches and a nip of Scotch to keep warm.

Golf is not about creature comforts, but comfortable playing partners. It’s not about flying your own Cessna to a landing strip and being shuttled into a gated reserve. It’s about driving over rutted dirt roads, finding an unobtrusive entrance and being immersed in the most important aspect of a great club – one with an exemplary, strategic golf course that recreates the conditions of the best UK and Irish clubs.

Since launching his first golf writing website in 2004, http://jayflemma.blogspot.com, Jay Flemma’s comparative analysis of golf designs and knowledge of golf course architecture and golf travel have garnered wide industry respect. In researching his book on America’s great public golf courses (and whether they’re worth the money), Jay, an associate editor of Cybergolf, has played over 220 nationally ranked public golf courses in 37 different states. Jay has played about 1,649,000 yards of golf – or roughly 938 miles. His pieces on travel and architecture appear in Golf Observer (www.golfobserver.com), Cybergolf and other print magazines. When not researching golf courses for design, value and excitement, Jay is an entertainment, copyright, Internet and trademark lawyer and an Entertainment and Internet Law professor in Manhattan. His clients have been nominated for Grammy and Emmy awards, won a Sundance Film Festival Best Director award, performed on stage and screen, and designed pop art for museums and collectors. Jay lives in Forest Hills, N.Y., and is fiercely loyal to his alma maters, Deerfield Academy in Massachusetts and Trinity College in Connecticut.

Story Options

|

Print this Story |