Featured Golf News

Vera Brupt asks, ‘Why do greens often have backing mounds?’

It’s somewhat ironic that Golden Age architects painstakingly fashioned approach areas in front of the green, when golfers used the running game. With aerial shots preferred and aesthetics more important, modern architects pay as much – or more – attention to the back of the green!

However, for good players, raising collar/rough edges with backing ridges to allow golfers to see the back of the green provides depth perception and definition and better shows green depth and pin location, which helps golfers plan their shot.

Backing mounds often stop lower-spin running shots of average players near the putting surface, while side mounds can direct marginally errant shots onto the green. In both cases, the “containment” these mounds provide keeps many recoveries shorter and easier, which speeds play.

Aesthetically, golf courses have controlled view points and sequences. Greens are the hole’s ultimate target, and should generally be the ultimate visual focus. On average sites, many greens need artificial enhancement of their setting and focus, and earthmoving is the simplest way to accomplish that, helping golfers to visually understand the hole. Where nature doesn’t provide trees or natural upslopes as a visual “end cap” to the hole, backing mounds serve the same function. Additionally, mounds integrate interior green contours with outside contours to create a “green complex,” rather than a green “sitting” on a site.

Building greens into mounds somewhat replicates early seaside links courses, where greens often occupied valleys between towering dunes. Critics of modern design recall that A.W. Tillinghast called manmade strivings “puny” in comparison to what Mother Nature provides, and it is often so true! Certainly, large natural backdrops look great, while artificially high green backdrops are often created in open areas to compensate for the lack of natural features, or to serve very practical functions like visually screening unattractive areas, or creating safety buffers for adjacent holes.

Earthmoving can be truly artistic, and many find the enhanced landscape more attractive than uninspired natural contours in many cases. As the famous landscape architect Hideo Sasaki said, “The earth is putty.”

The task of the golf course architect is to create ridges and mounds that reasonably mimic natural contours and provide visual enhancement to the hole, and provide playing assistance to the golfer.

The appearance of having moved very little earth is often the result of moving enormous amounts of earth to match nature’s scale. Long ridges with a flowing top require more fill but look more natural than mounds that are too small, artificially “cone-” – or “dome-” – shaped, or tie abruptly to native contours.

Placing the long axis of the ridge perpendicular to golfers, provides the most effect while saving earthmoving. A narrow ridge will appear the same as one twice as deep, since golfers don’t see the back side.

Ridges with 3-, 4-, 5- or 6-to-1 (33-17%) slopes are typical, but the last 20 feet should gradually flatten to 6-, 7- or 8-to-1 slope until blending naturally into existing topography, rather than have a steep slope that meets flat ground abruptly.

Generally, manmade ridges should mirror natural contour, being generally flatter on flat areas and steeper on steep areas. Keeping the high points near natural high points, and low points near valleys, and using maximum slopes that are not more than 2-3 times steeper than natural contour are good R.O.B.O.T’s to maintain a natural look. Overlapping ridge lines rather than ridges on a straight line are usually very attractive and naturalistic.

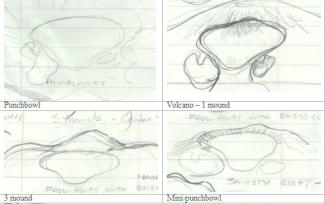

However, an occasional, extravagantly contoured green complex creates a distinctive green, especially if the previous or next greens are simply graded. I consciously vary the character by changing the heights, orientation, slope steepness, number and arrangements of green backdrop ridges, as the following sketches demonstrate.

|

|

|

Playability occasionally affects green backdrops, too. I generally favor higher backdrops on downwind holes and/or where green orientation is across the line of play, as there are more “over-shoots” there, and extra ridge height helps containment. Of course, certain design concepts – like punchbowl or Redan greens – require high backing ridges.

Overall, the ease of modern earthmoving has made golf course contouring one of our best design tools. While we often overdo it – many feel the period of the 1980s was one of earthmoving excess, most golf course architects have returned to a moderate, yet sophisticated level of earthmoving that enhances golf for everyone – since aesthetics is the one golf feature that everyone enjoys!

Story Options

|

Print this Story |