Featured Golf News

Colonial in Winter: The Yellow Rose of Texas

Texas sunrise: the pale, grey light of dawn slowly blossoms into broad, golden beams of sunlight. It's a new day, and as the sun slips over the horizon to shine a little light on Colonial Country Club, that's when the golf course begins to emerge from sleep and stretch golden arms of her own. Shimmering before us like sunlight on a rippling sea, Colonial blooms each winter morning like a yellow rose, dignified, graceful and hardy. Her dormant fairways a fine shade of "biscuit brown," even in somber late December, she glows warmly like a crown of glory, fairways gleaming with the fire of winter, each green an iridescent emerald bobbing in the ocean of tan Bermuda grass.

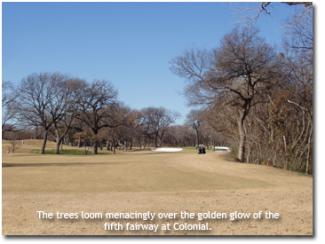

Yet the trees cast a different hue upon the landscape. Normally, verdant cloisters of broad leafy canopies, these bare branches loom close and menacing. Like a phantasmagorical scene from an Edgar Allan Poe tale, the trees make Colonial look ghostly: a desolate heath, a windswept plain. A cold gust bites fiercely, then wanes, then swirls around us again, giving a mournful howl. As if on cue, a single hawk flies its sentinel reconnaissance overhead with piercing and cunning eyes, hunting.

Still, a line of golfers stands on the range, eager as gun dogs, excited anticipation on each face. Bleak December dismays the trees, but not the golf course nor the buoyant hearts of the players. Architect Keith Foster had just completed renovations, the largest-scale and most extensive project undertaken at Colonial in decades; changes were made to every hole. Word around the club was that they were terrific. The members invested over $3 million, and everything got completed on time, under budget and in apple-pie order.

Basking for decades in the esteem of countless champions, Colonial is one of the most historic courses in the country. Home to Ben Hogan, host to the oldest PGA tournament continuously held at one course and the site of the 1941 U.S. Open, Colonial has been called one of the three best clubs on the PGA Tour by golf historian Chris Clouser (along with Riviera and Westchester CC). Indeed, with over 70 years of epic stories, the older, more venerable members find their reminiscences in great demand.

One common remembrance is a time when 320-yard drives didn't turn every course into a lawn-darts competition. Colonial, like so many great courses, needed to defend itself from the super-balls that pass for golf balls and the football helmets on a stick that pass for drivers. The club built its sterling reputation on being a course that rewards skill, not brute strength, finesse and thoughtful play, not bomb and gouge. So, without land to build new tees to re-craft it into an 8,000-yard behemoth, the members had to think creatively.

"We couldn't add raw distance," began Colonial's Matt Blake, "so we pitched some fairways back just a bit so that drives don't run out as much. This is designed to only affect players using the tips, not the other sets of tees. We also added bunkers to pinch landing areas on a few holes, and moved some bunkers further back so that they are still the same strategic challenge that the architects intended."

It worked. The course's length increased only 180 yards. With fairways contoured to prevent long rollouts and gigantic forward bounces that leave a flip wedge in, Colonial will still reward shot-makers. With greenside bunkers moved closer to greens, and fairway bunkers moved further out from the tee boxes, the course still plays as it has in years past. Foster also removed some trees behind the putting surfaces, and built green surrounds that can be "short-cut" to closely shaved areas to allow myriad options: bump-and-run, pitch-and-check, putt or chip.

Foster's tie-ins and shaping are natural and smooth. Most importantly, the course looks and plays as it has for many years. It may not be exactly the way the architects designed it when John Bredemus and Perry Maxwell first sent Colonial's founder Marvin Leonard various sets of routings in the 1930s, but the membership likes it, and it's a fair and interesting test for the PGA Tour event. The routing is essentially the same. But between re-channeling the Trinity River in 1968 and smoothing and flattening the greens so the pros don't get too frustrated, some of Maxwell and Bredemus's work has disappeared.

Even so, Colonial still remains a clever test of creative, patient, skillful golf, and is beloved in Texas (both for its heritage and Ben Hogan's). That was the reason for my visit, to write about Colonial's transformation as well as to learn more about Maxwell's role in building Colonial, regarded by many as one of the gems of his resume and, finally, to compare and contrast it with the great architect's other work.

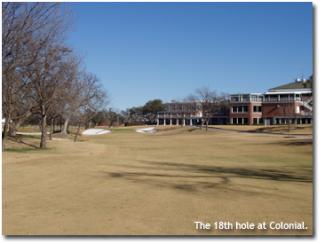

Everyone seems happy with Foster's efforts, especially the members, many of whom are safely inside on this crisp morning, sipping tea and enjoying breakfast. Some choose the old-school refinement of strawberries and cream, some savor the Colonial country breakfast - a bacon-and-egg sandwich, cheesy grits and biscuits - and others share laughs with their friends over huevos rancheros. A few feet away, the club Christmas tree glows, decorated tastefully with its simple but elegant red-velvet balls and white lights contrasting against deep-evergreen branches.

Those intrepid enough to brave the cold, however, are now milling about the starter's hut, waiting for their hole assignments. With a short delay for the frost to burn off, we are sent off in shotgun fashion. The starter calls the names off a list.

"Smith . . . you start on 8."

"Thanks, Joe," Smith (not his real name), responded. Two carts peel away from the line that had formed.

"Jones . . ." A tall, lanky redhead perks up inquiringly. "You're on 9." Off his group goes.

One by one, the ritual continues. As each group receives their assignment, then drives off, I do some quick math in my head, recalling the holes that are still waiting to be doled out. There are a few notables that have not been called. I put two and two together in my head, and realize with both fear and excitement that today two and two might just add up frighteningly to . . .

"Three!" Joe says triumphantly, beaming at me.

Unbelievable. How's that for luck? I'm gonna have a horseshoe imprint on my forehead before I've finished my morning coffee. Oh well, it makes good copy.

For those of you scoring at home, Colonial's hardest and most infamous stretch of holes is 3-4-5, the "Horrible Horseshoe." Two brutally long par-4s - the latter of which borders the Trinity River - sandwich a long uphill par-3. Their main defense is length.

Starting on three may have been the next best thing to starting on either one or six. Starting at the first hole you get to see the natural progression of the course as the architect intended. Starting at six, you finish at the Horseshoe, an unforgettable way to end the day. Starting on three might be a rough wake-up call, but it also showcases, arguably, the best and most famous holes first.

Happily, Foster's skillful and work shines through immediately, and at the most crucial point on the course - its heart and soul. Standing on the third tee, looking at the hard-left bend the fairway takes, the line between fairway and rough is so seamless it's almost imperceptible. The left side of the fairway - the shorter route to the green - now has a gentle bank, back and to the right, to soften the landing of a touring pro's draw off the tee. Yet it had no effect on my 3-wood shot to the middle of the fairway.

A badly-pulled long iron and a bladed pitch left me a downhill 35-foot putt. Here's where Colonial's sublime greens show their subtleties. The putt looks to break several feet right to left, but Jerry - our genial and well-informed caddie - reads a mere foot of break only. The ball rolls in the front door for an opening par. Jerry doesn't miss a read the entire day. To me, that's the first duty of a caddie. Ask for him when you visit Colonial.

The fifth hole has similar shaping and strategies. The landing area on this dogleg-right that closely hugs the Trinity has a gentle, almost imperceptible cant back and to the left, which prevents a long fade from running too far. Again, the line between fairway and rough is so gentle, so smooth that one has trouble determining where the fairway ends and the rough begins. The same is true of the fairway and the green: it's eminently natural. It also metes out penalties ruthlessly. I block my approach with a fairway wood only a little and the Trinity River makes my Nike Platinum disappear faster than a rabbit in a conjuring trick. Maybe a straight ball will get you in more trouble at Colonial than anywhere else, but my crooked ones sure didn't help either.

Other holes follow the same theme. The fairways on six and nine slope back and to the left toward the furthest set of tees, but had no effect on the shorter boxes set at different angles. The bunkers on seven, 12 and 15 close the front of the greens so tightly, you can forget about bumping and running the ball. Fairway bunkers are ready to snare poorly-struck drives.

"I see why all-star golfers win here with frequency," begins club guest Gary Wiseman, the drummer for Dallas rock band "Bowling for Soup" and an avid golfer, a 16 handicap. "When I missed a target on the approach, I was punished severely by the bunkers. The bunkering was excellent, beautiful and shrewdly placed. At some courses, there's a right side and a wrong side to miss on. Here, there's no right side to miss. Misses find a bunker and believe me, it is scary standing out there even in the middle of the fairway, the entrance to the greens is so slim and the bunkers so deep."

Nevertheless, even being turned into Texas Toast isn't enough to dim the outlook of either Wiseman or Chris Burney, the band's golf-loving guitar player, who also played with us.

"It was so exciting for me. I've dreamed of playing here all my life," Wiseman said gratefully, his face lit up by star-struck eyes and a broad smile. "It was everything I'd expected and then some. But it was also all-around tough. There is nowhere to hide out there."

Indeed, Wiseman is plucky. At one point, deep in the woods, he punches out between two trees, a razor-thin opening split by a laser-perfect shot. "That was amazing!" I said, impressed. "Did you move the ball back in your stance and shorten your swing to hit that?"

"No," Gary replied sheepishly. "I just closed my eyes and prayed."

Burney had a similar shot on the gorgeous par-3 eighth. The picture of him short and right of the green staring at an endless line of trees is iconic. Still, he agrees that Colonial's changes are flawless and the bunkers murder. "The course looks so natural, it's impressive that he [Foster] could make it look so smooth," Burney observed. Then his face fell into a look of frustration and horror. "It was hard," he admitted exhaustedly. "Those bunkers are tough, and the approaches are so hard. Everywhere I missed, there was a bunker." Then he brightens again. "It's a terrific finish from 15 on. I also liked nine. But despite it being so hard, there's no doubt it's the greatest course I've ever played yet. It's a masterpiece."

Well said, Chris. It is a masterpiece. And that's one Texas institution talking about another Texas institution, and they know institutions at Colonial. Take Hogan, for example. The club - Hogan's Heroes in this case - has a room dedicated to the man.

Visiting this area is a holy moment; I'll never forget it as long as I live. I'm seeing some of golf's ancient treasures. There's a wicker basket from Merion. In another case are replicas of the Wanamaker Trophy (that goes to the PGA champion), Claret Jug (British Open) and a U.S. Open trophy. I count five Colonial trophies and five matching medals. Ben even gave the club his shoes (size 9 ½).

On a darker note, the most compelling image in the collection is a photo of Ben being loaded onto the stretcher after his near-fatal car accident. The look on his face is surprising. He's awake and alert. A blanket covers him from neck to toes. But it's his expression that's mesmerizing. Hogan is wearing the same stoic, icy dignity and calm as he did while leaning on his putter. Once again, Hogan shows he was a rock during tough times. That's how he won 10 majors. Many people even think that in that photo, with his same steely resolve, Hogan looks exactly like Sean Connery. The "get well" bathrobe given him by George Burns, Bing Crosby, Harpo Marx, Leo Durocher and others sits next to it.

Best of all, Ben's locker is set up to one side. It's fully stocked. Several shirts - all grey or white, except one yellow and one light-blue - a mirror, towel, razor blade, shoes, watch, shoe bag, bag and clubs, and his plaid jacket are arranged in organized fashion, as though awaiting their owner at any moment. You can even see yourself in Hogan's mirror. Imagine what he saw . . .

Despite being a composite of holes designed by both Maxwell and Bredemus, the course is listed by most as a Maxwell course, especially after his revisions for the 1941 U.S. Open and the renown of the Horrible Horseshoe. There is clearly a great deal of Maxwell in the design, such as clamshell bunkers, numerous doglegs, judicious use of specimen trees and diagonal use of wash areas as hazards. Colonial also follows his broader tenets: it's eminently natural; utilizes as many of the site's severe natural features as possible; the variety of holes; and the routing give the course its character. But many of Maxwell's details in the greens may have been removed during subsequent tournament preparations.

Additionally, the scale of the course is enormous. The size and scope of its playing field closely resembles Bethpage Black, Oakmont and Winged Foot. The regulation-members tees play 6,700 yards, also similar to Bethpage. In the old days many par-4s were driver-3-wood-wedge holes for us mere mortals. The fairways are surprisingly wide. (Interestingly, back in the '40s the 50-yard-wide playing corridors were described by the press as "narrow.")

The "oversized" greens are absolutely perfect, smooth and true. Since touring pros don't like heavily undulating greens - even Tiger Woods once remarked, "I hate greens that have elephants buried under them" - the breaks at Colonial often look greater than they really are. That makes them tricky to read, and makes scoring difficult even though the course hasn't been "tricked up."

While the original architect was known for his "Maxwell rolls" - the massive undulations with confounding breaks at Southern Hills or Crystal Downs for example, Colonial's greens are tamer and more accessible to the touring pros that face them every year. They can only take Southern Hills's greens once every decade, not every year. But the soft tilts, twists and turns of Colonial are refined - a few inches here, a few inches there, much like Garden City Golf Club.

The benign greens and relative flatness of the course are the only major differences between Colonial and Southern Hills. The latter course enjoys better terrain and greens than Colonial. Oklahoma City Golf & Country Club is better still. But when comparing them side-by-side you see a striking resemblance. On the other hand, Colonial is a remarkably easy course to walk. Much wider in winter - with little rough and no leaves on the trees - it's more fun for the bogey golfer, and the fast firm conditions hearken back to the way Maxwell intended it to play when he built it.

Some might argue that winter is an even better time to play Colonial than in summer. With the trees bare one can see across many holes at once: vast expanses of the open plain on which the course sits. Texas's yellow rose blooms only in winter, and the magical shapes and hues created by the gold course and the pale brown of the dormant trees' bony arms are a stark setting in the still silence of a windless day. When the Texas winds howl, it's even more gothic. Tim Burton would join this club in a heartbeat.

If I might make a suggestion: a televised tournament should be hosted here in December. People have never seen a tournament in such conditions and it would be a new twist. Instead of the vacuous made-for-TV desert "shootouts" on lush-green courses, invite 32 stars to return for two days and play this venerable track at a time when it looks as though she's dressed for Halloween. Of course they'll come. The hospitality and history of Colonial rival any major championship venue, and the fans would find the contrast with the PGA Tour event in May fascinating.

Privately, perhaps for members and their guests, they could do something similar, or even throw two great tournaments/parties: one at Halloween to celebrate the course's changeover to gold, then another in February for the "rites of spring" to celebrate its change back to normal.

Either way, Colonial is versatile - it plays impeccably any time of year. The club should take great pride in its superintendent and maintenance staff. Foster's efforts to defend the course are first-rate, state-of-the-art golf-course-architecture problem-solving. Moreover, it's gorgeous. Who needs an evergreen tree in Texas? Colonial's yellow rose endures winter's chill so well, blooming brightly and proudly, just as she has for more than seven decades, a reflection of the same unconquerable spirit of her stewards.

Odds and Ends

There are only 87 bunkers on the course. Maxwell didn't need 180 when 80 or so more interestingly placed traps can defend the course just as successfully.

The fairways are dormant Bermuda 419, A-4 bentgrass for the greens (same as Baltusrol).

There are 20 different-sized jackets kept for tournament winners. Don't worry; they even have one that fits "Lumpy" (Tim Herron). They sometimes give out green jackets.

The trophy looks like something given away at a motor speedway.

There was a second Christmas tree in the clubhouse. This one was in the pro shop and was green, white and gold. Ornaments included tinsel and shiny, brand-new golf shoes.

Since launching his first golf writing website in 2004, http://www.jayflemma.thegolfspace.com, Jay Flemma's comparative analysis of golf designs and knowledge of golf course architecture and golf travel have garnered wide industry respect. In researching his book on America's great public golf courses (and whether they're worth the money), Jay, an associate editor of Cybergolf, has played over 220 nationally ranked public golf courses in 37 different states. Jay has played about 1,649,000 yards of golf - or roughly 938 miles. His pieces on travel and architecture appear in Golf Observer (www.golfobserver.com), Cybergolf and other print magazines. When not researching golf courses for design, value and excitement, Jay is an entertainment, copyright, Internet and trademark lawyer and an Entertainment and Internet Law professor in Manhattan. His clients have been nominated for Grammy and Emmy awards, won a Sundance Film Festival Best Director award, performed on stage and screen, and designed pop art for museums and collectors. Jay lives in Forest Hills, N.Y., and is fiercely loyal to his alma maters, Deerfield Academy in Massachusetts and Trinity College in Connecticut.

Story Options

|

Print this Story |