Featured Golf News

Interview with Jeff Brauer

Here's an interview session Cybergolf's Jay Flemma had with Texas-based architect, Jeff Brauer. Brauer has been a frequent contributor to Cybergolf, providing enough stories, articles and insight to have his own tab, Brauer's Book (www.cybergolf.com/brauersbook). Jeff has also contributed mightily to our Architects Corner (www.cybergolf.com/architectscorner) section. Here's Jay's interview in its entirety.

He's an ardent hockey fan, he's quick with a pun, he's partied with Dallas Cowboys owner Jerry Jones and, yes, he's won a best new course award as a golf architect. In a few short years since leaving the august firm of the Dick Nugent's family and friends - his Illinois mentors, Jeff Brauer has steadily climbed to the top of his profession, mixing a little bit of puckish fun with modern twists on old-time golf architecture strategies. Let's learn a little bit more about one of the rising stars of the next generation of great golf course designers.

JF: How did you first get interested in designing golf courses?

JEFF BRAUER: When I was a kid, my next-door neighbors belonged to Medinah. We snuck out there on a Monday, so my first round of golf was Medinah No. 3, a U.S. Open course. I fell in love with golf courses that day, and the ambiance of the club - at age 12, no less. I went home and told my parents I was going to be a golf course architect! I also remember my next round was on a public course with my dad. I sure could tell the difference.

JF: Be honest. What do you think of Medinah architecturally?

JEFF BRAUER: I still liked it, despite hearing how average it was supposed to be on www.GolfClubAtlas.com. I will say that I didn't care for the Rees Jones changes. While I understood them, it just didn't look like Medinah anymore. I thought the chipping areas, some of which drop off the green but are still elevated to the surrounds (like behind the first green), looked unnatural. The other thing I recall about Medinah was the ultra-deep bunkers. My first design philosophy was that I would use very few bunkers, but make them very, very deep, a la Medinah. Like the rest of the profession, I eventually went to more and shallower bunkers for the "look."

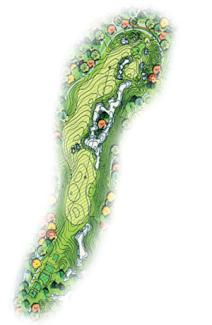

The 2nd hole at The Quarry at Giant's Ridge

JF: How did your career path proceed and when did you first begin to study the architecture of the old master designers?

JEFF BRAUER: Not long after my career announcement, the ASGCA happened to move their HQ to Chicago, and my Dad saw it in the business pages and wrote for info. I got a package along with an order form for more information. I ordered every pamphlet and book on golf course design I could find. There weren't as many in those days, but about the same time, Golf Digest had some architecture articles: one by Herbert Warren Wind extolling the virtues of Donald Ross's mounding and grass hollows and another by Gary Player on "what makes a golf course good." The only thing I recall from that article was his theory that of the four par-5s, one ought to be reachable by all, two should be 'tweeners' and one should be out of reach. Early in my career, that meant 500, 530, 560 and 590. Now, it means 540, 580, 620 and 660 or more.

The packet also came with the American Society of Golf Course Architects roster. I wrote Robert Trent Jones and got a nice letter back. I also wrote Killian and Nugent (being somewhat surprised to see a member in the next town over), and went in for an "interview" where they told me the basic plan to become an architect: get summer jobs with landscape companies for golf courses, pursue and excel in the study of landscape architecture, supplemented with turf classes, soils classes, surveying and site engineering.

I did all that, and they felt obligated to hire me when I graduated in 1977. I worked there until they split up in 1983 and spent the next nine months working for Ken Killian, mostly because I was mostly working with him on projects at the time. At the same time, we were working with Bill Kubly at the much smaller Landscapes Unlimited.

Only slightly off-topic, I somewhat disappointed my dad in turning down an invitation to attend Harvard after my Bachelors in landscape architecture from the University of Illinois at Champagne-Urbana. I had won the landscape architecture senior award of merit, which got an automatic invite. He couldn't quite see the golf thing and he really couldn't see turning down a scholarship to the most prestigious university around just to design golf courses!

Anyway, it didn't escape my attention that Ken was only six years older than I and had been in business . . . six years. I walked in to Ken Killian's office on my 29th birthday and quit. To avoid competing with him, get in what I thought was the "hotspot" of golf design, and access a southern-central connecting airport, I picked DFW to base my practice. My market research consisted of looking in the yellow pages of several big city phone books (again at my local library), and seeing that Dallas was the only one without a golf architect listed. Dallas, here we come!

I made a side trip home from the ASGCA meeting that year in Palm Springs, and picked out an office and apartment in a weekend. I went home, got married and moved back down to Dallas within a few months. I got my first job, again with some help from Mr. Kubly, who let me route a nine-hole course extension in Holdrege, Nebraska, that he was going to build. I did it on my parents' kitchen table, having already vacated my apartment!

Later, he helped again by introducing me to a few Dallas folks at Eastern Hills in Garland, east of Dallas. My second clients were Wichita Falls Country Club and then the city of Wichita Falls who came by when we were working at the club. I was on my way!

Within a few months, I got a call from a club near Shreveport, La., and the head of the selection committee was in the same boat I was, but in irrigation construction. He took pity on me, and realized that a struggling associate probably did a lot of the work of a bigger firm and hired me.

In quick succession, I got a similar call from Odessa, Texas, and when they heard I had worked on courses by Killian and Nugent, they hired me for the skill, proximity, and of course, lower fee. About the same time, I was getting some photos printed and ran into a local land planner, who told me a local city was doing an interview. I got that job by pushing my public course experience when some of the bigger-known firms pushed their "best work" rather than their public work.

A year later I was slowing down, napping a bit I think, when the phone rang and it was Larry Nelson's Dallas-based agent trying to save a long-distance phone call and get some info on Larry working with a golf course architect. I didn't let him get too far down the list. In 1987 Brookstone in Atlanta opened. It took until 1989 to secure a DFW 18-hole course, given how provincial Texans can be.

At the moment, I think I have designed 51 courses - although that includes nine-hole extensions, executive courses, etc. - but more than half are new 18-hole courses. I have done about twice as many remodels of various sizes and types, but less than 10 full-blown redesigns. Fast forward to today, and my current projects include Firekeeper in Mayetta, Kan., with PGA Tour player Notah Begay.

JF: Who are some of your favorite architects and why?

JEFF BRAUER: The two who come most quickly to mind are Mackenzie and Raynor, whose styles couldn't be more different. Mac was a whiz at bunkering and most of my bunkers look like his. I don't get to see a lot of Raynor courses, but they look so different and that alone makes them cool, even if the template holes may or may not work any more.

JF: A two-part question: First, give us some specific examples of bunkers you did that look like Mackenzie. Second, why might Raynor's template holes not work any more?

JEFF BRAUER: Any cape- and bay-style bunker is based on Mackenzie, like he did at Cypress Point or at No. 10 at Augusta. Each of the noses of turf comes in down the slope a different amount and at a different angle. The top edge had rhythm and flow, but he varied angles and heights. That's the difference between an average bunker and a great one. At Indian Creek I made sure the capes and bays came in at different heights and angles.

I also love TOC (the Old Course at St. Andrews) and NGLA(National Golf Links of America). I understand that some think they are museum pieces from a different era that can't be built again for reasons of golf moving on. I take certain lessons from them, but don't think rebuilding the Old Course in exact replica would be a good idea. Now, the Road Hole (perhaps on a par-5 as originally placed), or the Valley of Sin where the valley replaces a sand bunker, or the Principle's Nose bunkers (moved down the fairway), or the little mound in front of the fourth green and a few other ideas still work in altered form 500 years later.

JF: What important lessons did you learn from the architects who gave you your first jobs?

JEFF BRAUER: Starting with Killian and Nugent in Chicago, at the Kemper Lakes project in May of 1977, right after I graduated from U of I, I got one great lesson after another. I took a week off after college, tried skydiving, and then I hobbled to work. They were great mentors, and over the years I hear myself saying the same sorts of things to my employees that they told me.

In many ways, much of my work is subconsciously similar to theirs, despite the fact that I consciously have tried to move away from some of their ideas. Their lessons ran the gamut from the ability to engineer a course well on plan, to the need to make the final tweaks in the field, to how to run an office and project generally.

As far as design, they and I are pretty much WYSIWYG (what you see is what you get) guys, and despite the current nostalgia in some quarters for blind shots, I still follow those rules. I do believe in some more subtlety than they might have, believing that a course that has slopes and nuances that prove more interesting over the years. There is no reason to leave those out of even modest public courses. Yes, on any given day, there will be new players who might like a straightforward challenge, but there will be far more who play every day who want the course slightly different each time they play.

JF: What courses that you have played inspire you to imitate the same design concepts?

JEFF BRAUER: My favorite old-time courses are many Raynors, including Shoreacres, Royal Melbourne (Mackenzie), San Francisco (Tillinghast), and Seminole, (Ross, but a different look than Pinehurst, in fact more in line with Mac). I think you could say I am as influenced by aesthetics as play value, since all golfers enjoy a great-looking golf course.

As to specifics, I love the angled bunkers at Seminole No. 6 and the generally scattered look Mac got with his bunkers. I like the angled carry bunkers at SFGC and RM because now they are fairly easy to manage. If a carry bunker were built at 275 from the tips now and had little way around because the fairway was narrowed, I don't think that would be as charming. I generally place any carry bunker short of the maximum distance so more folks have that thrill.

It's hard to describe in words, but the contouring on those greens has been an influence on me. (H.S.) Colt greens influence me even more. The easiest way to say it is that 1970s' designers tended to build mounds on the inside curves of the greens, whereas Colt and others built them on the outside curves, which is a totally different look. It gives a random, rolling edge to the top edge of the green that is attractive to the golfer.

JF: Tell us about some of the most interesting holes on the courses you have designed, focusing on the public side.

JEFF BRAUER: I actually think of design in terms of "bits of this, bits of that." As a result, I have a big file of ideas. Perhaps the most direct influence on the Quarry at Giants Ridge was Mike Strantz's designs at Tobacco Road and Royal New Kent. Having a quarry site, I knew I needed some dramatic examples to convince my conservative clients that something more radical would work. I took them to both Pine Barrens and Royal New Kent to convince them. However, it was Strantz's work that convinced me to build holes like the second at the Quarry rather than clean up the ground and "sanitize it," as has happened on some other quarry courses.

Over the years, I have had the opportunity to work with a lot of public course management companies, though. When you factor in dollars and cents, their influence is still pretty strong on me. In a way, the Quarry is "Strantz Lite" as far as pure design features, whatever that is, but I think it hits the practical middle of great design features and playability for all.

JF: What holes, in particular, did you like at Tobacco Road and Royal New Kent?

JEFF BRAUER: The one that influenced Giants Ridge was number 2, a horseshoe par-5 at Royal New Kent which convinced me to build number 2 at the Quarry.

Third hole at Legend at Giant's Ridge with Footprint Bunker

I also love a lot of his ultra-long greens where the green is 50-60 yards long. Strantz did that a lot, so that concept became the 13th green at the Quarry and the third green at Cowboys.

JF: Where do you go to play golf for fun? For vacation?

JEFF BRAUER: When I play locally, I either play new courses I haven't played or go back and play my own. You saw that when we played together earlier this year in Texas. Basically, I prefer to see - to me - new courses. I guess my last golf vacation was last summer, when I went to Northern Michigan and played Crystal Downs, Indianwood in Lake Orion, Tullymore and Kingsley Club - two new and two old classics. I liked them all and learned something from each.

JF: What did you learn from each of them in particular?

JEFF BRAUER: From Crystal Downs (Mackenzie), that great kidney-shaped green at No. 7, it really wraps around. He also had one like that at Ann Arbor. I have a version of that at Firekeeper in Topeka, my latest project. I also like the first green at Crystal Downs, with the three bunkers on the high side, but a grass slope on the low side. No. 11 has a great two-tiered green where the shelf runs parallel to the axis of the green, it doesn't cut through the short axis but the long axis, making for really interesting putts.

Jim Engh's work is stout - we talk on the phone a lot. He followed me at Nugent. I see our shared heritage in our mutual training, like the grand scale of the courses - Dick liked them big - and then mounding around the greens, and Jim has used that as a nice jumping off point to make his own work have a unique style.

I played Kingsley with Mike DeVries, and almost every hole has some remarkable feature, it's just full of neat ideas. On one you hit over a center mound. Then he has a punchbowl green, he has bunkers hiding a small section of the certain greens, he just had interesting and unusual shaping and ideas that made each hole memorable.

JF: What is the first duty of a golf course architect?

JEFF BRAUER: There are a few duties that most golf architecture buffs don't think about. Job one is always safety, keeping holes far enough away and in good relationships to and from boundaries and each other that hair doesn't crawl up on golfers' neck from worry.

Circulation is also overlooked. Getting golfers from parking to the clubhouse and around the course efficiently contributes to speed of play and enjoyment far more than most people understand. In many designs, I have had the dilemma of taking advantage of the land features at expense of safety and usually opt for safety, especially when clear-cut issues exist. While a few golf course architects tout that the holes come first, the longer I go, the more I think that we need to take care of basics.

Once the routing is completed, naturally drainage is the top priority. I put more time into drainage than most. I once got a job by playing my course with the prospective client in the rain. Not only was it playable, but the ranger told them that they didn't miss a single tee time after a 3" rain, which wasn't the case when they played some other golf course architects courses on the same trip.

I always say that the design features which are fun for me to do and that golfers notice are really only the last 10% of my job.

JF: Where can we find their footprints of older, great architects in your work?

JEFF BRAUER: As mentioned above, the vast majority of my bunkers replicate the Mackenzie style, even if some are softened just a bit in the name of maintenance. But as I play and study older courses, I keep finding little "bits" of genius. For example, last time I was at Prairie Dunes I noticed that the green surrounds basically tied back into the surrounding hills as quickly as possible, which was an influence. My training was to grade surround earth forms to the green itself, but I realized that I could get a much better effect by grading them to the angles and shapes of the surrounding land forms, which had the side benefit of creating a lot of those interesting Ross-type chipping areas.

JF: How did your life and career arc change after Giants Ridge opened to such great acclaim?

JEFF BRAUER: Honestly, I wish it would have changed more. While the courses got great acclaim, I think if they had been closer to a big city it might have resulted in more people seeing them and talking about them.

JF: Tell us about the building of the Minnesota courses?

JEFF BRAUER: The first was what is now called the Legend at Giant's Ridge. The "Legend" is the story of a Bigfoot-type monster that used to roam the area. I used that to inspire a large footprint bunker on the third hole. It's a sharp dogleg par-5 with a shortcut route. The area needed to be a hazard and was narrow, so a "foot" fit perfectly, although I only put in four toes.

The third at Cowboys has a green much like Mike Strantz built - long and thin - testing distance, instead of accuracy

The course also features a beautiful par-3 over Wynne Lake. The course was designed as a "gentle giant" and is intended for pleasant resort play. The course ran into some environmental lawsuits before getting built. So, when it came time to build the second course (based on the success of the first), we examined several sites and chose an abandoned quarry. Oddly, one side of the road was an iron ore pit and the other side was a sand and gravel quarry, as it straddled two different geologic areas. Because it was a scarred site, environmental permits were easy to obtain and protests were minimal.

Another difference we wanted was to design a tougher course at the Quarry to offer a distinctly different experience. The length and difficulty, along with the totally different sites, led one critic to muse that it was hard to believe the two courses were designed by the same person, which I consider a high compliment.

Perhaps the biggest surprise on the brawny 7,200-yard Quarry Course is how much finesse is required. You are often "playing the contours" with your shot. On the 18th green, you can play well left of the green, where a "kick-in bank" directs such shots right to the pin, without flirting with the old mine pit water hazard on the right.

As an aside, it's a state-owned course, so they originally featured locally made products, including "coiled bratwurst," which is said to be more practical than the long kind, since you don't need to buy two kinds of buns. While tasty, it resembled dog poo too closely to enjoy the flavor.

Near the end of the Quarry construction project, the nearby Fortune Bay casino began interviewing golf course architects and they selected us to design their course, giving us marching orders to "split the difference" between the two courses at Giant's Ridge. I crafted a course with similar length and shot values as the Quarry, but in look and feel it looks more like the Legend. It has a massive scale and is also blessed with views of Lake Vermillion and some rock outcroppings (some of which had to be blasted) to give the course a unique character.

I like all three courses equally, and opinion among golfers seems to be split as well. Each plays off the other and most golfers come up to play all three. I knew they were going to be destination resorts, but also that two of three had great natural looks. The Quarry had a great unnatural look. The routing had to find holes in distinct drop-off areas as opposed to the gentle rolls of the other two sites, but the process was really similar.

It was the first time I had to consciously make the courses different from each other. While I have designed so many courses in DFW, so many were for the local market that I didn't feel a particular need to try for distinguishing features.

JF: Tell us about the interesting architectural features at Cowboys.

JEFF BRAUER: Jerry Jones only told me to give him a traditional course. I guess if he was giving instructions now, he would add "don't let punts hit the scoreboard." Since I had done so many courses in DFW when this one came up, as it was to be a top-line course, I struggled deciding on style. However, it is a spectacular site for DFW, and we didn't feel the need to go over the top anyway. I went for a traditional look and more green contours than the typical course, as if they course had been built years ago.

Probably the most popular holes are the elevated tees on Nos. 2 and 4. The long par-5 13th is a favorite of mine. It reminds me of so many old holes where the natural trees make the corridor so narrow. I also like the first. The green is sort of a reverse L-shape, which is somewhat based on the 10th green at Prairie Dunes.

JF: When is it permissible to try to improve what you found on an earlier course when you are doing a restoration, renovation or redesign? Even if the old architect was a master?

JEFF BRAUER: I think it's always a goal to improve. There is a place for total blow-ups, even on courses of the old masters. Sometimes, the here-and-now owners need a new look for marketing purposes and only a new look will do. In fact, restoration probably works best marketing-wise when the course had gotten away from the original look so that old is new again.

So much has changed, and any design decision involves value judgments. If trusted to make them, I make them and take them seriously, but in the end, the redesign must work first and foremost for those paying dues or greens fees now and into the future. Some examples include removing a bunker because it interferes with changed traffic flows due to cart use now. Except on a very low-use course, it probably has to go, perhaps replaced with a similar one in a different location. All golf course architects and clubs make those decisions. Some people presume that certain golf course architects make better decisions in this regards than others, but the decisions have to be made.

That said, it's usually pretty clear that being sympathetic to the original style usually makes sense. Adding modern mounding on smaller sites, for instance, usually looks forced in.

JF: Have your thoughts on golf course design changed over time?

JEFF BRAUER: Absolutely! I'm still pretty firm on having 18 holes . . . other than that, anything goes!

I reached a point a few years ago when I questioned what I was doing. As mentioned, Killian and Nugent were great mentors, but they couldn't be right about everything and they did warn about following your own rules too closely over time. I realized at one point that I was probably doing certain things out of habit, and thus becoming repetitive, and I didn't want to be the guy where you could say "Oh, another Brauer course."

Strangely, perhaps, my cure for following rules too much came in the form of writing even more rules for myself. I started writing for www.cybergolf.com and contributing to different books and magazines on my father's old saying that if you can't explain something fairly quickly, it's probably not a good idea. At that point, I couldn't really articulate why I did certain things, so I set out to find out.

I ended up doing a theoretical analysis of tee shots, approach shots, putts. Basically, presuming that on most holes golfers want to use driver, I started noodling on possible strategic scenarios in their basic form. I came up with well over 20 good ones (and some not so good ones, but there is no reason to visit those!) and began to wonder why so many courses - mine included - had such repetitive tee shots?

In essence, the golf course architect can ask the golfer to carry, skirt or lay short of a strategic hazard, and presuming most holes have at least a few degrees of dogleg, the key hazard can be on the inside or outside of the bend, on both, staggered or absent. So, why do so many holes then, have a single bunker on one side of the fairway at the landing zone?

I guess I forced more variety on myself by creating some of what I call "hip pocket" concepts, and others might call templates. The fear is that a golf course architect would force them on the land, but it's easy enough to find land to support most of them, starting with the holes I have routed that "cry out" for a certain hazard pattern, and filling in the rest on more mundane land.

JF: Give us some specific holes as examples.

JEFF BRAUER: As I was routing the quarry, I had a cape hole at No. 8 that had a natural cut for that hole. The green is a Mae West, "peekaboo" green by cutting into the ridge and angling it. The first hole also has a turbo boost if you want to take the more dangerous road on the right of the fairway rather than the wider left side. The par-4 third hole at the Quarry has a reverse Redan-ish green, because I used the natural slope on the left to effectuate that shot if the player so chooses. I also like long par-3s with smallish greens to test long-iron play (or a fairway wood), so No. 4 at the Quarry. We shaped the green like the Liberty Bell because I drew up the plan for that green on 9/11.

I also went through the same exercise on approach shots. I prefer most of my greens to be of the "Sunday pin" type, with a lot of the green open to the run-up shot, but one (or two, which I dub the green a weekend green) spot well guarded by hazards. These greens aren't too taxing on average players, but are flexible enough to set the course up tougher when warranted. But there is room for small "precision greens" and larger greens with multiple targets within a green.

JF: What mistake would you like to have over again?

JEFF BRAUER: Like most golf course architects, I started out taking whatever project came my way. And those were low budgets and eventually, when people start looking at hiring you, they see some projects you would rather not have them see! That happens to a lot of us, and it seems like one poorly executed low-budget project outweighs the impact of five great ones.

JF: What is the strangest, zaniest thing you have ever had to deal with while trying to build a golf course?

JEFF BRAUER: When I was building Wild Wing, the Japanese owner - who supposedly didn't speak English - asked through a translator why my cart path was on the left side of the hole instead of the right side. My explanation was, "Because the green is a double-green with another hole! Otherwise we would have had to split the green in half or tunnel under." He was the first one to laugh and no translation was needed!

JF: What is the best hole you have ever designed and why?

JEFF BRAUER: I like the short par-4 holes at the Quarry all about equally well. I especially like the sixth and ninth because they are so different than what I normally do. I used the scarred land that was there and made it into something.

JF: What is the most creative solution for a problem you've encountered in your design projects?

JEFF BRAUER: The drainage at Wild Wing Plantation is probably the best. Willard Byrd had done the first two courses, and had invested about 400,000 cubic yards of fill to raise fairways for drainage. I opted to use a system of linear lakes, connection pipes and drain basins to build the Avocet course closer to grade. Thus, for my 475,000 cubic yards of earthmoving budget, I was able to get the client more "fru-fru," which was his major design objective to distinguish his third course from his first two.

JF: Uh…"fru fru?" That's technical jargon for…?

JEFF BRAUER: Fancy stuff!

JF: What do you think are some of the best values in golf right now?

JEFF BRAUER: Many good upscale designs of the last decade are dropping their prices. You can play some pretty good, if not great, golf in most big cities for under $60 with cart.

JF: Name some of your favorite examples.

JEFF BRAUER: University of Michigan, Cog Hill, (Dubsdread, although I don't think it's under $60), my course Sand Creek in Newton, Kan., is only $36 and ranked No. 2 in the state. Tobacco Road and Royal New Kent are great architecture and dramatic, as well as reasonably priced. I love Finger, Dye, Spann, and Black Mesa in New Mexico is super, and so is Paa-ko Ridge, also in N.M.

JF: Ben Crenshaw aside, why do most (touring) professionals design courses that don't really resonate well with ardent golfers?

JEFF BRAUER: I sort of object to the leading part about Ben. I think his courses are great, especially when they work on a great site. But I am, frankly, NOT sure that their low-key style resonates with the average golfer. I also object to the assumption that the professionals actually design the golf courses! Most have a guy like me in the background who does most of the work. I am impressed with Notah [Begay] in that we spent more time talking about concepts and details than I ever have with a pro.

It's hard to generalize, really, but if a course doesn't resonate, it's probably because the big names get the real estate courses and in general, few housing-related courses are going to be real high on any national list.

JF: Some architects say that you have to compromise and make trade-offs pretty much at every course. Can you recall some moments that you had to make some trade-offs that you were concerned about initially that actually might have worked, just specific examples from some courses that you built?

JEFF BRAUER: I could tell you hundreds. It really is all about compromise, and there really isn't anything that I would call pure design, absent of real-world compromises.

For specific examples that actually worked, the footprint bunker at the Legends of Giant's Ridge was an example of the owner trying to talk me out of it. Now that they have sold a bazillion dollars of logoed shirts with that footprint, they may have been glad to have agreed with me.

When I first proposed it, it was called cheesy. But I needed a long skinny bunker to fit the spot and create the optional carry. Adding toes to it to suggest the legend of the giant that used to roam here was just a comedic bonus. I even tried to get a second one in to suggest the large leg span of the giant, but was shot down on that one.

Just the other day, Notah asked to add a bunker to help lead the eye to the ninth green at Firekeeper. I told him that doing so would block off the cart path already constructed and only marginally add to the visual effect. He understood and we left it out.

The fifth at Cowboys is one of the few holes I consider to be "just" a transition hole. We had to fill it about 10 feet to get it over an old quarry and above the flood plain, just to get from the nice land on the 4th hole over to the nice pecan grove over on 7-9.

JF: How do you deal with the dilemma of restoring a course to its old design, but with technology advances still making it challenging to the best golfers?

JEFF BRAUER: I haven't really done much restoration work on classic courses. But, as I said, it's a value judgment. The few we have done usually don't present real problems on most holes, but in a few cases moving the tees back, then moving the bunkers out a bit, but still in similar land forms, then rebuilding the green with similar surrounding contours and general flow (perhaps flattened a bit).

There are always a few holes that you can't do that and keep the same feel, and then there is always at least one hole where you wonder if the original architect missed his train for the site visit, was trying something new, or just messed up. Those are the hard ones, because there are cases where there is clearly a better idea that we would like to go with.

JF: Do you think that television has a bad impact on architecture because people tend to associate prettiness and opulence with great design?

JEFF BRAUER: Since I have known golf, there has always been television. It's all I know. I think TV has made us more visual as generations grow up and pass on and that is reflected in golf course design - it has to be more visual and on par with the best of the Golden Age in terms of bunkering and land movement. At the same time, I don't think we need special effects like explosions!

The basic design principles are still the same, but until recently, more and more courses employed them to keep up with the Joneses. After all, business says you build a better mousetrap to succeed, so it does happen. At the same time, clubs and balls, and the reduced thought that seems to come with seeing too much TV have led to reduced - or at least different, strategies than the Golden age. Maybe all our courses are like beauty queens now.

But overall, I am hard pressed to wax nostalgic on what we have lost. I don't think you can take a few examples of great courses going away or being remodeled unsympathetically and say that we paved paradise. We are still creating modified versions of paradise, just like the back yard is a modified version of an English garden.

Comparing what we have to visions (most of us can't say memories) of what courses "must have been like" is a no-win situation for a new course. But, when I look at old photos, I am not sure these aren't the good old days. Part of me would love to be offered higher-end club jobs, remodels for U.S. Opens a la Rees, etc. But I am not a member of the elite golf course architecture squad. Now, if you go to places like Kansas, Nebraska, Minnesota and DFW, I think most people would say I helped elevate the level of golf in those areas where I have worked. If my career ends and that is my legacy, I will be happy with that, rather than a string of top 100 courses. Nothing is wrong with providing quality, affordable public golf on more than an occasional basis!

Photos and drawings courtesy of Giant's Ridge Cowboys Golf Club.

Since launching his first golf writing website in 2004, http://www.jayflemma.thegolfspace.com, Jay Flemma's comparative analysis of golf designs and knowledge of golf course architecture and golf travel have garnered wide industry respect. In researching his book on America's great public golf courses (and whether they're worth the money), Jay, an associate editor of Cybergolf, has played over 220 nationally ranked public golf courses in 37 different states. Jay has played about 1,649,000 yards of golf - or roughly 938 miles. His pieces on travel and architecture appear in Golf Observer (www.golfobserver.com), Cybergolf and other print magazines. When not researching golf courses for design, value and excitement, Jay is an entertainment, copyright, Internet and trademark lawyer and an Entertainment and Internet Law professor in Manhattan. His clients have been nominated for Grammy and Emmy awards, won a Sundance Film Festival Best Director award, performed on stage and screen, and designed pop art for museums and collectors. Jay lives in Forest Hills, N.Y., and is fiercely loyal to his alma maters, Deerfield Academy in Massachusetts and Trinity College in Connecticut.

Story Options

|

Print this Story |