Featured Golf News

Is the Battle of Sharp Park Finally Over?

On December 6th, 2012, United States District Judge Susan Illston found moot claims brought by a group of environmental organizations, led by the Center for Biological Diversity (CBD) and listed in a March 2011 lawsuit, that the San Francisco Recreation and Parks Department (RPD) was in violation of Section 9 of the Endangered Species Act. The environmentalists contended that, by pumping water off the fairways at Sharp Park Golf Course in Pacifica, Calif., during times of flooding, the RPD was exposing California red-legged frog egg masses to the air, causing fatal desiccation of the egg masses, and thereby reducing the frog population. They also claimed that other golf course operation activities - lawn mowing and golf cart usage - harmed the frog and the endangered San Francisco garter snake by running them over.

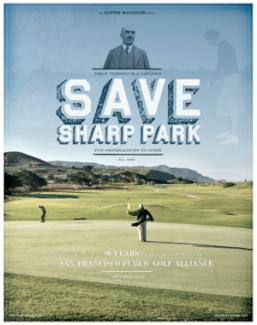

San Francisco Public Golf Alliance Poster

In short, the environmentalists were accusing San Francisco Rec & Parks and the golfers who played at Sharp Park - designed by the great Alister Mackenzie and opened in 1932 - of being responsible for the death of a rare species. They concluded that the course must close, and supported the notion that the space left behind should be managed not by the City of San Francisco but by the Golden Gate National Recreation Area - a part of the National Parks Service whose anti-golf perspective is well known.

The fight between the conservationists - a dedicated and persistent band marshaled by the CBD but also including the Wild Equity Institute, a San Francisco-based nonprofit founded in 2009 by former CBD employee Brent Plater and devoted to securing environmental justice, and the Sierra Club, whose focus - admittedly - leaned more towards preservation of the frog and snake rather than the removal of golf, and those wishing to retain the course, had raged for over four years. (Use of the word "raged" may seem a little excessive for a debate involving golf and frogs but, make no mistake, the two sides fought their respective corners with the intensity and zeal usually reserved for Presidential races.)

Plater, vehemently golf-averse, at least where Sharp Park was concerned, based his arguments not only on the perceived damage being done to the endangered creatures. He was also adamant that Sharp Park Golf Course was a major financial drain on the city, and that it had lost so much of its character through the years it wasn't worthy of being maintained anyway.

"Nobody in San Francisco cares about Sharp Park," he told SFWeekly in June 2010. "If that golf course were to fall into the ocean tomorrow, nobody would blink an eye." Then, in a Wild Equity press release dated November 16th 2010, he added: "No community center or neighborhood park should have services reduced while the (Parks) Department is subsidizing suburban golf in San Mateo County. We deserve better. It's time to close Sharp Park Golf Course and bring the funds saved back to San Francisco's communities, where the money rightfully belongs."

The San Francisco Garter Snake

Plater also made reference to the book "Missing Links" by respected golf writer Daniel Wexler, who said there is little left of Mackenzie's original design. "According to Wexler," Plater added, "all but a handful of the original links have been altered or destroyed."

On the surface at least, Plater and his fellow environmentalists built a strong case, one that was adopted and reinforced by the San Francisco Board of Supervisors, an 11-member legislative body within the government of the City and County of San Francisco, and whose Jon Avalos (of District 11) formally proposed that ownership and control of the land on which the course sat be transferred to the federally-controlled National Parks Service.

But as the would-be course-closers joined forces and established their position, the pro-golf lobby was amassing its own forces under the unofficial leadership of Richard Harris, a highly respected San Francisco lawyer who, along with friend and fellow golf-supporter Robert "Bo" Links, formed the San Francisco Public Golf Alliance in 2007 with the goal of safeguarding municipal golf. Far from wishing to retain city-owned courses at the expense of the environment, the alliance made it clear on its website that it sought to "preserve affordable, eco-friendly golf" and that its plan "includes a commitment to improve the natural habitat," while preserving public-access courses.

The alliance's first task was to help protect Lincoln Park GC, whose future looked very uncertain at one point. But the group's attention soon shifted to Sharp Park once the seriousness of its predicament became clear, specifically following the CBD's move, in September 2008, giving the Rec & Parks Department 60 days to comply with the Endangered Species Act or face legal action. (It is not clear why the CBD took two and a half years to finally issue the lawsuit, and no one from that side of the debate would tell us.)

As it turned out, one of the golf sponsor's most effective weapons was a non-golfer who had never played at Sharp Park and probably has no plans to in the future. Karen Swaim, a biologist considered to be the foremost authority on the ecological characteristics of the coastline at Sharp Park and its suitability as a natural habitat for the frog and snake, addressed the Board of Supervisors in December 2009 and stated, explicitly, that because the area was predominantly brackish prior to the early 1940s when the first sea wall at Sharp Park was constructed, it was very unlikely that either the salt-intolerant frog or snake were present before the course was built. Asked by Supervisor Sean Elsbernd, who had been a vital figure in the push to restore Harding Park Golf Course - perhaps San Francisco's finest public course and venue for the 2009 Presidents Cup, if she would have said the same if working for the Golden Gate National Recreation Area rather than the San Francisco Rec & Parks Department, Swaim was unequivocal. "Absolutely," she responded. "You need to protect the sea wall and have a managed freshwater habitat for the species to recover. And that's all there is to it."

The California Red-Legged Frog

In March 2011, however, Plater disputed this, saying Laguna Salada, around which much of the original course moved, was historically a brackish/freshwater lagoon and not a tidal saltwater lagoon; that the golf course did not create the freshwater habitat; and that the sea wall is not necessary for the continued protection of the endangered species. It was a curious stance, however, given the fact that Swaim's statement to the Board of Supervisors 14 months before had included slides showing that in 1928 the land surrounding the lagoon was flat agricultural fields used for the production of artichokes and therefore not suitable as a garter snake habitat; that by 1946 (following construction of the sea wall) red-legged frogs and garter snakes had appeared and begun to be documented; and that in 1988-89, following breaches of the sea wall caused by El Niņo storms, the frog population was wiped out, resulting in the snake population being similarly decimated owing to a lack of food.

Science wasn't the only factor working in the golf community's favor though, as it held some pretty significant political cards, too (the position of Jon Avalos and the Board of Supervisors notwithstanding). On December 13, 2011, the Supervisors voted to enforce the transfer of management of Sharp Park to the National Park Service, but six days later San Francisco Mayor Edwin Lee vetoed the ordinance. In a letter to the Supervisors, Lee said he believed in "striving for an equilibrium between environmental and recreational needs" and that envisioning the end of golf operations at Sharp Park was "not a balanced approach."

In January, Avalos moved to override Lee's veto, but found only five supporters among his fellow Supervisors when he needed seven. Lee's predecessor, Mayor Gavin Newsom, was also a staunch supporter of keeping the golf course, as were the Pacifica City Council (though located in Pacifica, Sharp Park is operated by the City of San Francisco); the San Mateo County Board of Supervisors, which has said it is prepared to enter an agreement with San Francisco to renovate and take over management of the course; the City of San Bruno; and the San Francisco and Pacifica chambers of Commerce. Democratic Representative Jackie Speier also went on record saying she did not support the notion of federal money (i.e., the National Parks Service) being used to manage Sharp Park. (It's interesting to note that Loma Prieta - a mountain in Santa Clara County - Chapter of the Sierra Club also supported keeping the course open.)

PROSAC, the City of San Francisco's Park, Recreation and Open Space Advisory Committee, appointed by the Board of Supervisors, also came down heavily on the side of golf. Having conducted a series of public hearings on all aspects of Sharp Park at monthly meetings from July through December 2009, it voted 15-1 in favor of the Rec & Park's plan to restore habitat, while keeping the golf course open. It also voted 13-2 in favor of pursuing cooperation at Sharp Park with the City of Pacifica and San Mateo County, but not with the Golden Gate National Recreation Area. On December 17, the San Francisco Recreation and Park Commission unanimously voted to adopt the recommendations of PROSAC's report, agreeing that the course should remain open and also be renovated, while abiding by certain directives to protect the frog and snake habitats.

Culturally, the golf course scored major points too, being designated a "historical resource" by the San Francisco Planning Department, and being recognized as historically and culturally significant by the City of Pacifica, the Pacifica Historical Society, and the Washington D.C.-based Cultural Landscape Foundation, which described Sharp Park as an "At-Risk Cultural Landscape."

Former U.S. Open champion and broadcaster Ken Venturi got involved by accepting an invitation to become the honorary president of the Public Golf Alliance and, in an open letter to the city's golfers, said it was "unthinkable that San Francisco would seriously contemplate the destruction of that Alister MacKenzie masterwork," urging them to defend the course with their money, time and passion.

Sharp Park GC from Mori Point

Numerous golf clubs, the Mackenzie Society, and eminent golfing bodies also let their voices be heard. The Northern and Southern California golf associations gave the course their backing, as did the USGA, whose Executive Director, Mike Davis, wrote to Mayor Lee shortly after the Board of Supervisors announced its resolution, to hand control of the course over to the Golden Gate National Recreation Area. "This would not only deny a recreational resource for a remarkably diverse population of golfers in the San Francisco area," said Davis, "it would be the demise of one of America's most precious public golf courses."

Daniel Wexler said something similar, taking issue with the manner in which Plater had used his description of the course in his book. The author publicly defended Sharp Park's historical value, called for its restoration, and criticized Plater for misrepresenting both the spirit and intent of his words. In a letter addressed to "Whom it May Concern," Wexler said that Sharp Park was one of just two municipal course that Mackenzie ever built and one that "any city would be thrilled to boast of," adding that, "with a bit of restoration and marketing, Sharp Park could easily become a drawing card for the City of San Francisco, resulting in economic benefits well in excess of simple green fee revenue."

Golfers who actually play the course did their bit too, attending the public hearings, appearing in YouTube videos stating their wish to keep the course open, contacting elected officials, circulating petitions, and becoming members of the San Francisco Public Golf Alliance, while donating to its work.

Richard Harris says the involvement of local golfers was vitally important. "Brent Plater and the other environmentalists have always tried to convince the public that golf is elitist and that Sharp Park caters only to wealthy white people," he adds. "They could not be more wrong. A hugely diverse cross-section of people play at Sharp Park - Chinese, Filipinos, African-Americans, blue-collar whites, seniors, women and juniors, and they pay very affordable green fees. Many couldn't afford the much higher rates of some semiprivate/resort courses in the area. That's why Sharp Park is known as the 'Poor Man's Pebble Beach.' "

He would never suggest it, but while all the above stakeholders' contributions most definitely had a favorable influence on Judge Illston's decision to dismiss the plaintiff's case, it was perhaps the role Harris played that proved most valuable. During the "conflict," the Stanford graduate who also graduated from the Boalt School of Law at UC Berkeley in 1977, said he hoped those in favor of keeping Sharp Park GC open know "what we're up against." But while the conservationists' weight and power continues to be felt in courtrooms up and down the land, it was perhaps they who failed to realize just how dynamic and potent a force they were facing.

Harris started out in journalism and public affairs consulting, and served in South Vietnam (1969-71) as a First Lieutenant in the U.S. Army (82nd Airborne Division and 25th Infantry Division). He is known as a tenacious litigator who led the successful legal campaign to save the Stanford Golf Course from a housing development in 2000.

Ken Venturi Is the Honorary

President of the Public Golf Alliance

One can only speculate at how far the "Save Sharp Park GC" movement would have gotten without Harris's organizational skills, knowledge of legal affairs and love of golf, not to mention his determination. But it's likely the outcome might not have been quite so satisfactory for golfers. Harris read, analyzed and responded to every single concern, complaint and accusation his opponents made, combing the RPD's budget spreadsheets in particular to get to the bottom of the issue surrounding Sharp Park's financial performance.

"The thrust of Mr. Plater's argument is that there are too many golf courses in the Bay Area, that Sharp Park loses money, and that City of San Francisco golf monies would be better spent on other San Francisco courses," he says. "These are political arguments that he and the other organizations have made unsuccessfully since the fight over Sharp Park started. Mr. Plater and the CBD make a big play on the figures but neglect to mention the 'overhead,' which is listed on the spreadsheets and made up of things like the mayor's salary, accountants' salaries, garbage pick-up, and so on. The overhead always exceeds any 'loss' the course makes, so the final deficit/surplus figure is not actually an accurate representation of how the course is performing. If the course did shut down, the overhead wouldn't go away, but would simply be passed on to other city services like children's playgrounds, for instance."

A look at the most recent spreadsheet available bears Harris's comments out. In the financial year 2010-11, Sharp Park showed an actual deficit of $90,029, but the cost of the overhead was $204,813.

By the middle of 2012, it was clear that no matter how strong a case against golf at Sharp Park the environmentalists were making, the case for keeping it was just that much stronger. The final nail in the environmentalists' coffin came in October when the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service sent a 57-page report to the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers documenting its Biological Assessment of golf course activities and how they affect frog and snake habitats. In the report, the FWS stated that golf at Sharp Park is "not likely to jeopardize the continued existence of the California red-legged frog or San Francisco garter snake," and that harassment and other "take" (pursuing, shooting, shooting at, poisoning, wounding, killing, capturing, trapping, collecting, destroying, molesting or disturbing) of frogs and snakes at Sharp Park does not constitute violation of the Endangered Species Act.

The report also proposed 32 conservation measures that should be adopted in order to ensure the long-term safety of the endangered species - measures such as reducing or eliminating pesticide/fertilizer use, reducing vehicle speed and activity (maintenance vehicles and golf carts), reducing the frequency and location of mowing, monitoring water-pumping and ensuring appropriate water levels to keep frog egg masses hydrated (even at the risk of flooding the course), constructing new habitats (specifically ponds), etc.

Brent Plater took some solace from the report, referring to the "50 pages of terms and conditions that burden the golf course with hiring biological monitors to walk in front of mowers, building new breeding and feeding ponds, and restoring habitat to establish a corridor between Laguna Salada and the Golden Gate National Recreational area."

A Woman Golfer circa 1930s at Sharp Park

But the list of proposals was not 50 pages long (that was the entire USFWS report) and, as Richard Harris points out, the San Francisco Rec & Parks Department already follows many of them. "For the most part, these conditions are the same self-imposed restrictions that the RPD already has in place," he says. "The conservationists simply aren't aware of the measures we and the RPD have taken to help the frog and snakes survive. We want to preserve and protect them in the lagoons and adjoining wetlands, and we support the city's plan to recover and enhance the natural habitat." Harris also added that the Public Golf Alliance had been working with the city's environmental stewardship experts, and had retained its own expert in the field, Dr. Mark Jennings, who was one of the people to petition for the frog to be listed as an endangered species.

While those favoring the upkeep of the golf course have clearly made a concerted effort to work with the environmentalists, it seems the favor has not been returned. "There are true believers among the most radical of the conservation groups who fundamentally dislike golf and want to see it eliminated, starting with Sharp Park," says Harris. His Public Golf Alliance partner, Bo Links, goes further. "I know I'm a partisan in the fight," he says. "But the sad truth is that folks on the other side are so rabid in their zeal they have lost all perspective."

So what now? Well, doing nothing at all except for complying with the instructions of the Army Corps of Engineers is certainly an option. But the way is clear for an overdue restoration of the course. A2009 report by the RPD, entitled the "Sharp Park Conceptual Restoration Study," showed a course remodel would actually be cheaper than creating a nature reserve. "The study showed that renovating the course would cost between $6 million and $11 million," says Harris, "but that a nature reserve would cost anything between $9 million and $23 million, much of which would be spent on digging up and removing the very invasive kikuyu grass on the fairways."

Also in 2009, Plater put forward the possibility of building a mitigation bank which, he said, might earn the city more than half a billion dollars. "Credits were selling last year at $3.5 million per acre for wetlands restoration," he said. "There are 200 acres that could be restored at Sharp Park (out of about 400). That's $700 million in gross revenue."

Harris disputed this figure, however, saying it was "fanciful." "Mr. Plater's theory was totally debunked by San Francisco's mitigation bank consultant, Westervelt Environmental Services, which said that a mitigation bank at Sharp Park would not have good prospects because the costs would be high, the benefits uncertain, and it would preclude all public recreational use of the property."

Following Judge Illston's December 6th verdict, the course restoration looks the most likely option but, of course, it won't happen without a good deal of strife and bitterness. Plater for one is hunkering down for a sustained struggle this year, posting this message on the Wild Equity website: "There will be more legal challenges and legislative work on this campaign in 2013," he says. "So stay tuned as we restore Sharp Park."

What that means is Jay Blasi, a former design associate at Robert Trent Jones II's firm who Harris and Links approached for an opinion on how golf, frogs and snakes could coexist and who now heads his own company. Blasi will lead the project but is under no illusions it will be an easy job or happen quickly (Bo Links says it will happen at BST - Bureaucratic Standard Time).

"It will be very complex and involve many different governmental agencies at the local, state and federal levels," says Blasi. "The regulatory agencies and the political decision-making bodies in combination will ultimately dictate what the golf course restoration project will involve and when it will start. There is no set timeline, but our goal is to work collaboratively with the governmental decision-makers and agencies to move forward as soon as possible with a plan that restores Alister MacKenzie's historic golf course, while maintaining and recovering habitat for the endangered species."

Although storms destroyed several of the original holes within 10 years of the course opening, and four holes were built (by MacKenzie's former assistant Jack Fleming) east of Highway 1 in 1941, much of the original routing still exists, says Blasi, but with a different numbering scheme. "Many original features - green contours, tees, bunkers - have lost their details over time, however," he notes. "Our goal is to preserve the existing holes, recapture original details in greens, surrounds, bunkers and tee areas, and hopefully even resurrect one or two of the long-abandoned original holes that now lie fallow in the dunes beside the sea wall."

Also consulting on the job will be Jim Urbina (and perhaps Tom Doak, too), who has a good deal of experience working at MacKenzie courses in California, having advised Pasatiempo, The Valley Club of Montecito, and Claremont CC on how best to restore and retain the classic features of their layouts.

Urbina first saw Sharp Park about 25 years ago when he and some colleagues were studying Cypress Point on the Monterey Peninsula. They would drive up to Pacifica to see a MacKenzie design that so few people had heard of. "It wasn't very high on the radar," he says. "But it was still worth seeing."

Sharp Park Foursome

Urbina walked Sharp Park with Richard Harris in 2010 and, in the clubhouse, saw a black-and-white photo of it from the 1930s. "It was amazing to see how the original holes looked," he says. "It was evident to me the course possessed many MacKenzie trademarks. And it was clear he considered what I call 'looking through the green,' basically what the golfer would see in the distance beyond the hole - the ocean, certain buildings, trees etc."

The course he saw two years ago had definitely lost some of its flavor, Urbina says, before adding it still had great potential and that he would like nothing more than to restore it to its full glory.

"That's probably impractical though," he says. "We have to take into account what is worth doing and what is expendable. When I was in the clubhouse, I didn't hear people discussing MacKenzie's 13 strategies. They were having fun just talking about their round and ribbing each other. So it would probably be a waste of money restoring every last MacKenzie detail. But it's important to remember he built courses for members; golfers, not championships. He loved St. Andrews and really understood the virtues of beautiful, affordable, and fun yet challenging, golf."

Neither Blasi nor Urbina know yet exactly which holes will be restored or what will be done to those that are revitalized. But the long-term goals will be to create a superior course to the present version, maintain affordable rates, and secure safe habitats for the Californian red-legged frog and San Francisco garter snake.

"Resolving the various issues at the golf course will be tricky, and will undoubtedly take time," says Richard Harris. "But Sharp Park is a treasure in the world of public golf. It is on the map, and people around the world care about it. Restoration of Alister MacKenzie's design is going to happen. And when it does, it will be glorious."

Tony Dear is an Englishman living in Bellingham, Wash. In the early 1990s he was a member of the Liverpool University golf team which played its home matches at Royal Liverpool GC. Easy access to Hoylake made it extremely difficult for him to focus on Politics, his chosen major. After leaving Liverpool, he worked as a golf instructor at a club just south of London where he also made a futile attempt at becoming a 'player.' He moved into writing when it became abundantly clear he had no business playing the game for a living. A one-time golf correspondent of the New York Sun, Tony is a member of the Golf Writers Association of America, the Pacific Northwest Golf Media Association and the Golf Travel Writers Association. He is a multi-award winning journalist, and edits his own website at www.bellinghamgolfer.com.

Story Options

|

Print this Story |