Featured Golf News

Second Stop: Cabo's First Resort - Palmilla

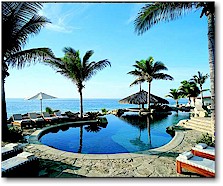

Next up on my tour of Cabo's golf courses is Palmilla, located a stone's throw from San Jose del Cabo, the more traditional of the two major towns on Baja's tip.

Originated in 1956 with its elegant, white-stuccoed hacienda, Palmilla achieved cult status in its early years as a popular getaway for dignitaries like President Dwight D. Eisenhower, Bing Crosby and John Wayne. Guests arrived by yacht or flew in to a small runway by the resort. Sportfishing was the game of choice in those early days, and it helped indoctrinate visitors to Cabo's charms for the first time.

Of all the resorts in Cabo, Palmilla was probably the most responsible for enlightening Americans to the area's great weather, spectacular scenery, and relatively easy access. It also became Cabo's first official golf resort with the opening of the first Jack Nicklaus-designed 18 in 1992. The two nines that comprise the original course, now dubbed Arroyo and Mountain, were complemented with the Ocean nine in 1999. The resort is owned by Goldman-Sachs and Kerzner International. Based in South Florida. the latter firm also owns the posh Atlantis Resort and the Ocean Club in the Bahamas.

Creating "Wows"

Anni and I were joined for our round on the original 18 by Ray Metz, a Kansas City native who's the club manager of Palmilla's golf operations. Ray's been at Palmilla since June 2002, but has been in Mexico for three years, having held the same title at Cabo del Sol when Troon Golf managed that facility the previous two years.

Ray, 44, has a unique background in golf and hotel management, having been a Class A pro since 1986. He says most of Troon's managers share the same type of professional experience, with the emphasis being on providing guests a first-class outing. Ray says his goal mirrors Troon's mission to ensure the first impression of the golfer's experience contains a big "wow" factor.

That introductory period includes driving in, dropping off clubs, paying green fees, going to the driving range, and heading to the first tee. Each step along the way golfers are greeted by well-dressed and attentive staff. Extra attention is paid to trimming the green areas and the first places seen while entering the facility. One of Ray's first moves at Palmilla was to repaint the entry sign.

Troon Golf was founded in 1990 by Dana Garmany, who at the time was the head pro-general manager at Troon North Golf Club in Scottsdale. Garmany's philosophy for Troon's facilities is to make golfers feel like a "member for a day," with the emphasis on value for price paid. Since many golfers can only afford to play a high-end course once a year, Garmany said let's make that experience special so he or she will want to return the following year.

Besides the initial "wow" factor, Troon Golf pioneered the concept of tournament-quality conditioning for its courses. Metz said that many players who visit Palmilla ask whether there's a tournament going on that day. To promote this concept, on a daily basis the cups are painted white, new pin sheets are printed, and every golfer gets a yardage book gratis. The philosophy must be working because Troon Golf now operates nearly 150 courses - owning some of them - around the world.

Labor & Tariffs

At Palmilla Ray oversees a staff of 95, 63 of whom are on the greens crew headed by superintendent Randy Bobbitt. This is a remarkable number considering that Ray and Palmilla - unlike Cabo del Sol - operates out of a small cabana-style clubhouse with no significant food service. Ray is assisted in the golf operations by a team of assistant pros, many of whom are temporarily transferred to Cabo from Troon's North American courses that are shut down for the winter. The company feels this helps retain employees while facilitating off-season training.

Wages for Palmilla's workers - and the employees at other Cabo courses for that matter - range from $7 to $25 a day, depending on the skill set required for a job. The guys who greet you upon arrival at the drop-off area earn 10 pesos (roughly $1) an hour. Their income is greatly influenced by the tips they receive. The marshals on the course are mainly retired Americans who work eight-hour shifts without pay in exchange for lunch and a free round of golf, a value of about $200 at most Cabo courses.

Hiring and overseeing workers is one of Ray's biggest challenges. For instance, he has to be careful when hiring beverage cart girls. Most everyone here takes public transportation and doesn't know how to drive. Even though a candidate speaks passable English and has good "people" skills, Metz has to make sure she can negotiate a beverage cart over Palmilla's winding, up-and-down concrete paths.

Cabo has become a prime destination for Mexicans seeking employment. People arrive with their families from throughout the country and often live under the same roof. They work long enough to save up a nest egg, then return home. Mexicans rarely direct animosity at Americans, who represent 95 percent of the golfers on Cabo's courses. There's also very little theft, drugs and crime because of the Mexicans' reliance on American tourism. The Mexicans are smart enough to know that if Americans sensed Cabo was an unsafe place, they won't come back to visit.

Mexico has labor laws that generally mirror those of the U.S. For example, Ray's special background in agronomy and management entitles him to a visa that allows him work in the country. On the other hand, his wife of nine years, Peggy Kellum, a former vice president at Titleist by Corbin, a clothing line based in New York City, is precluded from working because officials feel her position could be filled by a nationale.

Many visiting golfers to Cabo are alarmed at the pricey merchandise in the pro shops. Most believe the steep prices are merely commensurate with the high cost of golf. That's true to a certain extent. But the steep green fees in Cabo are due mainly to the area's high operational costs. Though labor is cheaper, the courses need more workers because of the amount of handwork required. In addition, most of the maintenance equipment used to condition the golf courses comes from America. Whether replacement parts or new equipment, each American product shipped into the country is taxed (more on that later).

Also, the cost of water is considerably higher than in the U.S. While Cabo's other courses use recycled water, the irrigation source for Palmilla and nearby Querencia is the San Lazaro Reservoir. Metz says that during the summer, Palmilla will use 3.5 million gallons a week on its 123 acres of turf. Troon uses a "deep and infrequent" method of watering for the 27 holes, which limits water usage while encouraging the bermuda turf to "learn" to be hearty.

As for the pro shop merchandise, the vast majority of it comes from the U.S. as Mexico simply doesn't have manufacturing companies geared for the golf industry. A duty is paid on all imported American goods, and the tariffs vary with the type of product ordered. If the Mexicans deem that a product can be ordered from inside the country, the buyer must pay a higher tariff. For example, if Ray orders golf pencils from the U.S., the Mexican government determines the same product can be ordered internally and affixes a 100% tariff on the pencils.

Ray orders most of his stuff from a sales rep in Southern California. He says you won't find any golf clubs or bags because the duty is simply too high and no one would buy them here.

As an example of how the prices for golf gear skyrockets in Cabo, take the case of a logo shirt. When a shirt (Cutter & Buck, Ashworth, etc.) is ordered from the rep, it must go through customs where it's retagged to show it went through customs. A duty (upwards of 35% of the shirt's wholesale cost) is imposed, and the order is loaded onto an 18-wheeler and trucked to Cabo. By the time it gets to Palmilla (a process that can take 3 months and result in out-style-clothes) all those extra steps - combined with the duty - result in a $68 shirt in the U.S. going for $88 here.

Ray & Peggy

During our stay in Cabo we made fast friends with Ray and his wife Peggy. Ray's work in golf management has literally taken him around the world. With his previous employers, Marriott (12 years), Hyatt (three years) and now Troon Golf (four years), Ray's previous stops as either the head pro, director of golf or general manager include Rancho Las Palmas (Palm Springs), Boca Raton Resort & Golf Club (Florida), Tierra del Sol Country Club (Aruba), Whittaker Woods (New Buffalo, Mich.), Morgan Run Resort (San Diego), Woodlakes Country Club (San Antonio), Maderas Golf Club (San Diego), Cabo del Sol Golf Club and now Palmilla in Mexico.

Peggy also has an extensive background in golf, having worked at Wilson Sporting Goods before arriving at Titleist. Peggy, a native of Indiana, is one of the pioneers of the golf industry when she became one of the first women to break into this male-dominated business in the 1980s.

The two met after Ray was deemed to be a "problem account" by Titleist when he was at Rancho Las Palmas. They sent Peggy in to smooth things over, and she took Ray and his staff to dinner. Shortly after, they fell in love and began a six-month transcontinental commute before getting married in 1993.

Among the couple's more interesting stops was Aruba. Since Tierra del Sol was the only golf course in the country, it was big news whenever something happened at the club. One day Ray and Peggy's picture would be on the front page of the newspaper with a dignitary and everything would be just peachy. However, if an employee was fired and made his disgruntlement public, Ray's picture would be on the same paper's front page the very next day and the editors would be asking for the American's head.

Also in Aruba, gas was a rare commodity and electricity was consistent, whereas in Mexico the opposite is true. It's rare to find electric golf carts in Mexico because of the spotty service. When Ray had a cargo of new electric carts shipped into Aruba, it became big local news.

The natives had never seen such a soundless vehicle and couldn't figure how the things worked. When the first cart was unloaded, the locals were in awe and the word spread quickly. Engineers working in the clubhouse came out and opened the engine compartment to see what caused the cart to go.

As for Cabo, Ray says the area has bounced back from 9/11 better than other tourist destinations, such as Cancun, Puerto Vallarta and Europe. He says it's because if something that tragic happened again, Americans feel they wouldn't have to rely on airplanes and could get home easier.

Oh Yeah, the Courses

As noted earlier, Palmilla has three different nines, the original Mountain and Arroyo and the newer Ocean. The first two are generally straightforward, with perhaps the Mountain offering more intrigue due to its ascending and descending holes and more shot options. Both contain a bunch of forced carries off the tees, with the routes broken up by escapable transition areas or down and dirty barrancas where it's unsafe for humans in search of golf balls.

Ocean, on the other hand, is an altogether different beast. And a beast it is, with lengthy par-4s, wild topography, and mind-boggling vistas that confuse golfers in their distance-to computations. Ocean was hurt by a late November storm that unceremoniously (and uncharacteristically for this time of year) dumped over 2 inches of rain on Cabo. The nine holes were temporarily closed due to some washouts, but the course was soon up and again beguiling players the first week of December.

Arroyo's first three holes made a liar out of me. In my previous Cabo del Sol dispatch, I said the bulk of Jack Nicklaus-designed holes favor the power fader. Wrong. Arroyo's introductory triad is all dogleg-lefts, with the inside of the turns outlined by waste bunkers that sit about three feet below the velvet fairways. Oh well. Give me a bogey - along with all the others I've racked up down here - on that one.

Speaking of Confounding . . .

All of the golf turf - fairways, greens and tees - in Cabo is bermuda. The grass grows 24 hours a day, causing all sorts of headaches for golfers unfamiliar with the stuff. Because of the turf's constant growth, a single green will contain grain that goes in all different directions, causing all sorts of doubt and putting woes.

Ray Metz says there's an imaginary line that defines which type of turf can be used in the Western Hemisphere. Cabo is located at a latitude of approximately 22 degrees and not far from the equator. Other strains - such as bentgrass - cannot survive Cabo's hot summers, which hover at around 95 degrees 24 hours a day.

My advise to golfers visiting Cabo for the first time? Don't worry about the grain. Simply line up shots as you would at home, and stroke putts based on their running up- or downhill. Don't get too down on yourself after misreading the grain, and realize that a steady diet of two-putts is acceptable here.

Besides, how can anyone get angry in paradise?

Next up is a brief look at the former Cabo Country Club, which now has the fancy moniker of the Raven Golf Club at Cabo San Lucas.

Story Options

|

Print this Story |